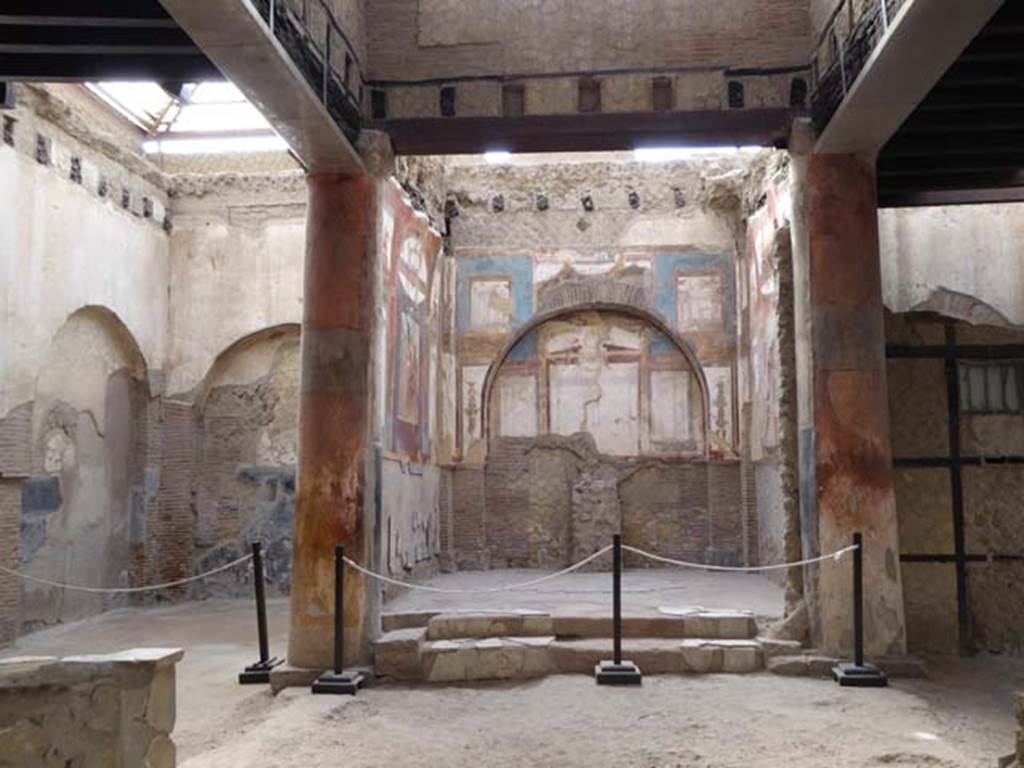

Herculaneum VI.21, Sede degli Augustali or Hall of the Augustales, linked to side entrance at VI.24.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2009. Looking south-west towards doorway at VI.24. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. October 2014. Looking south. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Looking south. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011. Looking south. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2006. Looking towards the south-west corner.

VI.21 Herculaneum. September 2015.

Looking south towards wall of Opus craticium, belonging to a possible caretaker’s room. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

On the west side (right) of the shrine was the caretaker’s room, in Opus craticium.

A skeleton, perhaps of the caretaker, was found here lying on the bed.

VI.21

Herculaneum, March 2014. Detail of column on west side, looking east.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019. Detail of column on west side,

looking west.

Foto Annette

Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. September 2015.

Looking south towards wall of Opus craticium, belonging to a possible caretaker’s room.

Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2014.

Looking south towards wall of Opus craticium, belonging to a possible caretaker’s room.

Foto Annette

Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2011.

Looking south towards column on west (right side) of wall. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

VI.21, Herculaneum. March 2019. Detail of wall in Opus craticium.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2006. Looking north across “caretaker’s room”, with remains of skeleton on its bed under a glass case.

Deiss wrote that this room had a door and a small rectangular window.

The window is placed high and is barred.

In the room was a wooden table of good quality and an elegant wooden bed.

On the bed is the skeleton of a man who had thrown himself face downwards in defence against the volcanic gases…….

The supposition has been advanced that the little room was occupied by a caretaker or priest, and perhaps due to illness, he was unable to escape.

If the man was a caretaker, why should he have a temporary room adjoining the shrine? Why furniture of such high quality?

If a priest, why not a room of more impressive construction?

Why would the chief server at an emperor’s shrine be left behind on the flight of his fellows?

And if these living quarters, in spite of their hurried construction, were intended to be permanent, why no stove, no brazier for winter, no latrine?

Neither hypothesis takes account of the barred window or the evident despair in the man’s position.

It seems apparent that he could not escape, and no one unlocked the door…….

Whatever the reason for the man in the barred room of the Augustales, in the end he too paid with his life.

Perhaps someday a chance reference in literature will provide the key to that strange little room and its hopeless occupant.

See Deiss, J.J. 1968. Herculaneum: a city returns to the sun. UK, The History Book Club, (p.155).

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2009. Remains of skeleton lying on bed in “caretaker’s room”.

VI.21 Herculaneum. January 2020. Remains of skeleton lying on bed in “caretaker’s room”. Photo courtesy Pier Paolo Petrone.

A team led by Pier Paolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at the Federico II University in Naples, determined that the victim’s brain matter had been vitrified, a process by which tissue is burned at a high heat and turned into glass, according to the new study. The fragments presented as shards of shiny black material spotted within remnants of the victim’s skull.

A study of the charred wood nearby indicates a maximum temperature of 520 degrees Celsius (968 degrees Fahrenheit). "This suggests that extreme radiant heat was able to ignite body fat and vaporize soft tissue," the study said.

The resulting solidified spongy mass found in the victim’s chest bones is also unique among other archaeological sites and can be compared with victims of more recent historic events like the firebombing of Dresden and Hamburg in World War II, the article said.

The flash of extreme heat was followed by a rapid drop in temperatures, which vitrified the brain material, the authors said.

"This is the first time ever that vitrified human brain remains have been discovered resulting from heat produced by an eruption," Herculaneum officials said.

See Mount Vesuvius blast turned ancient victim’s brain to glass on the Archaeology News Network.

See Heat-Induced Brain Vitrification from the Vesuvius Eruption in c.e. 79 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

VI.21 Herculaneum. January 2020. Vitrified brain material found in skull of skeleton lying on bed in “caretaker’s room”.

Photograph ©

Parco Archeologico di Ercolano.

Discoveries of cerebral tissues in human remains are rare archaeologically speaking, according to the report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

And when they are found, they are most likely to have been "saponified", meaning converted to soap over time.

But the brain of one person who perished in Herculaneum found in the 1960s on a wooden bed under volcanic ash in a building known as the Collegium Augustalium reportedly experienced a different fate.

The researchers say they discovered shards of shiny black material in the victim's skull, which appeared to be the remains of brain tissue converted into glass by heat.

They worked this out by testing the shards and analysing the proteins found within them, confirming them as proteins known to be found in the human brain. The experts also tested what appeared to be the victim's hair, finding fatty acids generally present in human hair.

However, "glassy material was undetectable elsewhere in the skeleton or in the adjacent volcanic ash, and it was not found in other locations at the archaeological site".

Together, these discoveries indicated the thermally induced preservation of "vitrified human brain tissue", the experts said.

According to the report, archaeologists also analysed charred wood at the site, which revealed temperatures reached a maximum of 520 degrees Celsius in the building the person was found in.

"This suggests that extreme radiant heat was able to ignite body fat and vaporise soft tissues; a rapid drop in temperature followed," the report reads.

One of its co-authors, Pierpaolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Naples Federico II, told The Guardian that vitrified remains of the brain had never been found before.

He told the publication of his discovery: "I noticed something shining inside the head."

"This material was preserved exclusively in the victim's skull, thus it had to be the vitrified remains of the brain. But it had to be proved beyond any reasonable doubt."

See Mount Vesuvius eruption so hot it 'turned victim's brain to glass', archaeologists say on MSN

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2006. West wall.

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Looking towards the north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Looking towards the north wall in north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2011. Looking towards the north wall in north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2010. Looking towards the north-west corner.

VI.21 Herculaneum. March 2019.

Detail from upper north wall on east side of plaque in north-west

corner.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. March 2008.

Looking towards the north wall in north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2006. Looking towards plaque on north wall in north-west corner.

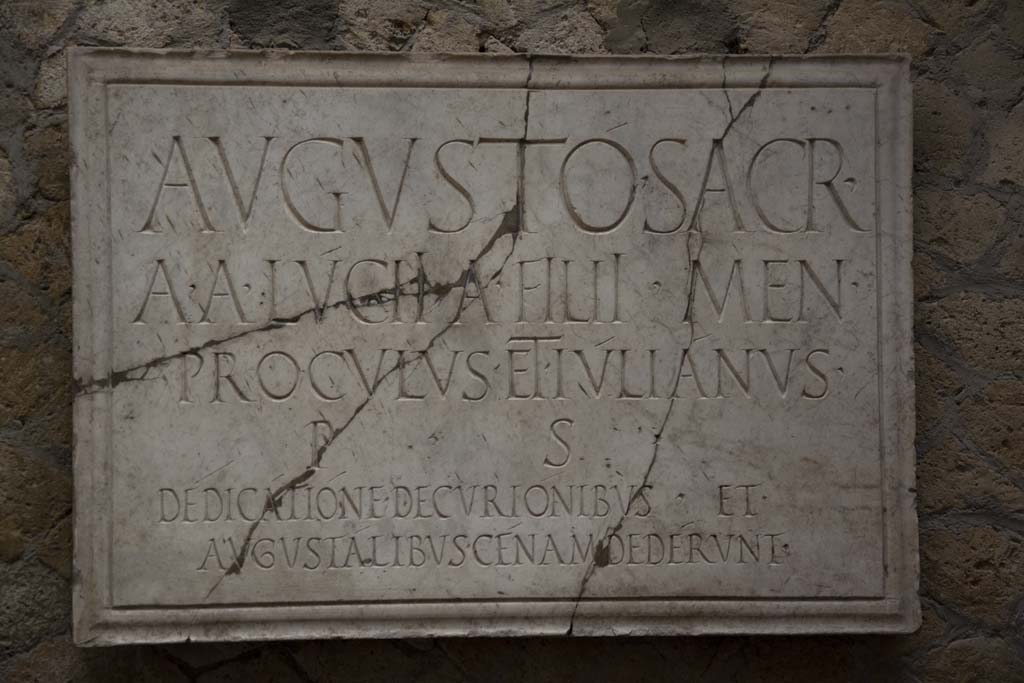

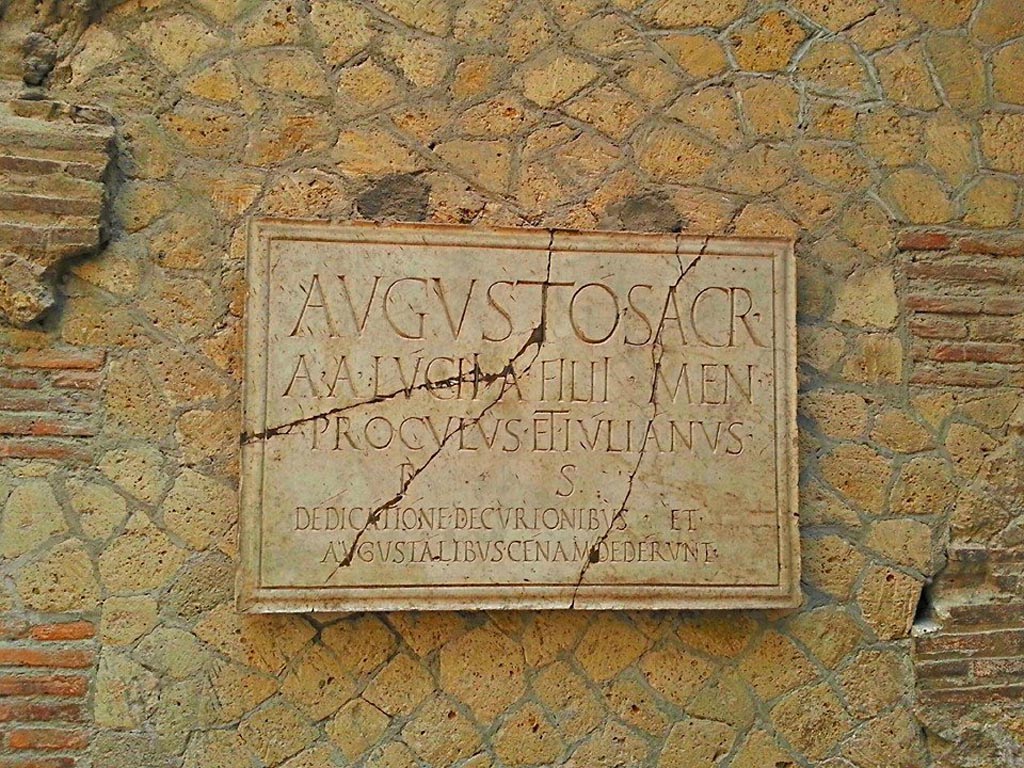

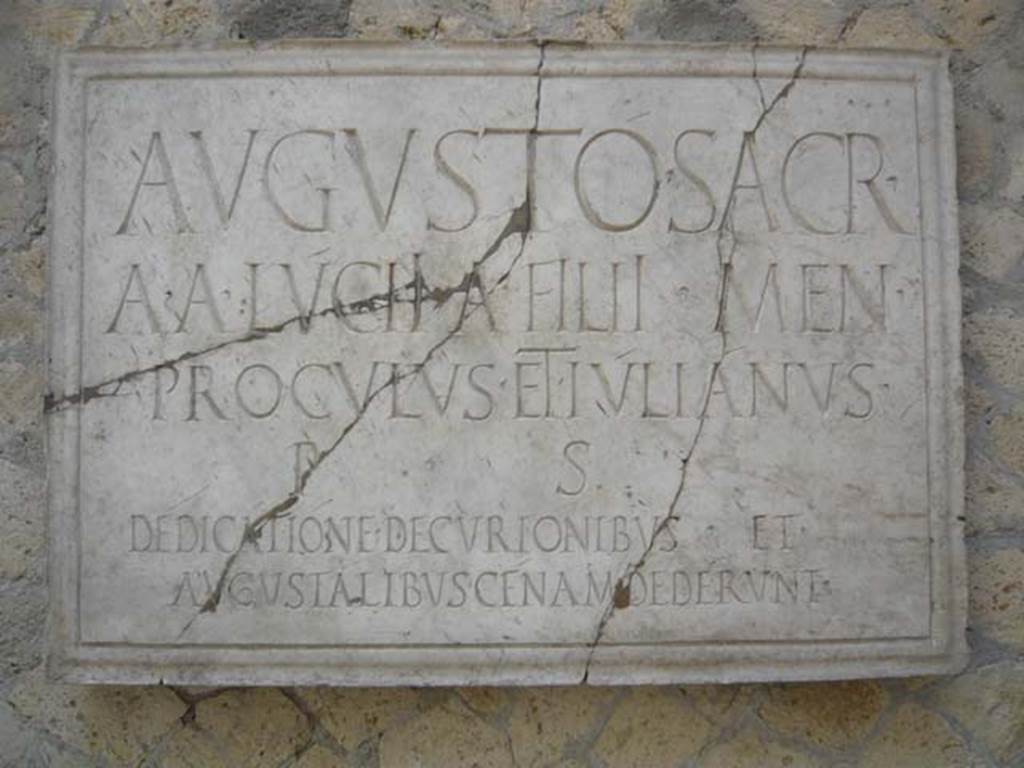

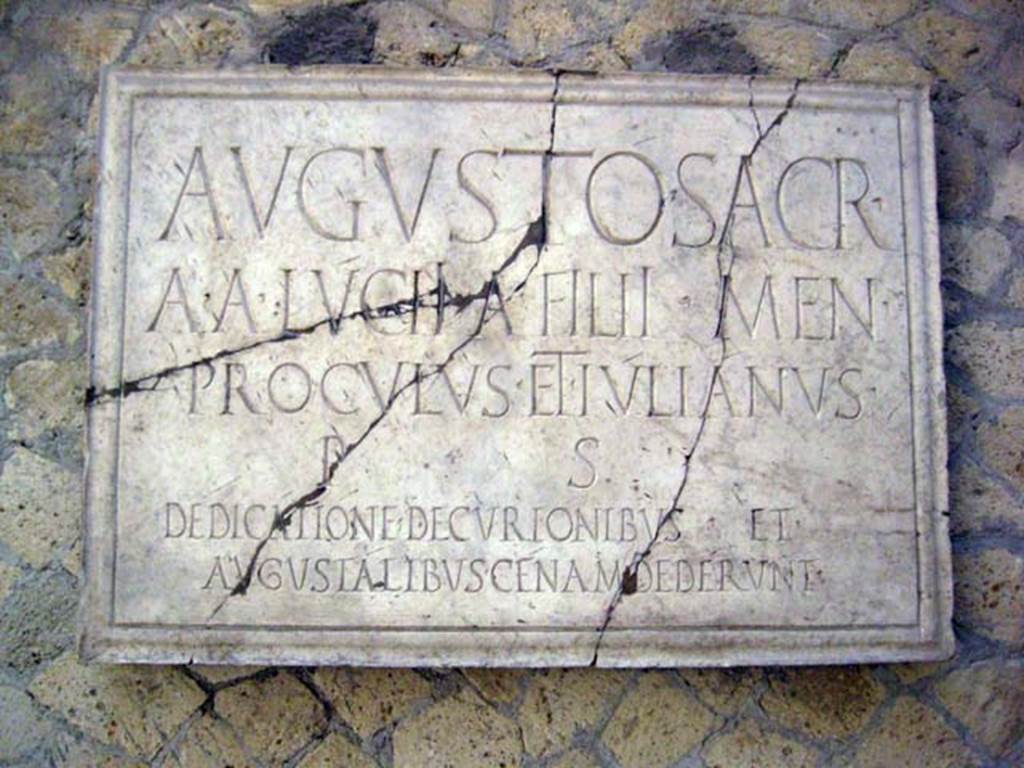

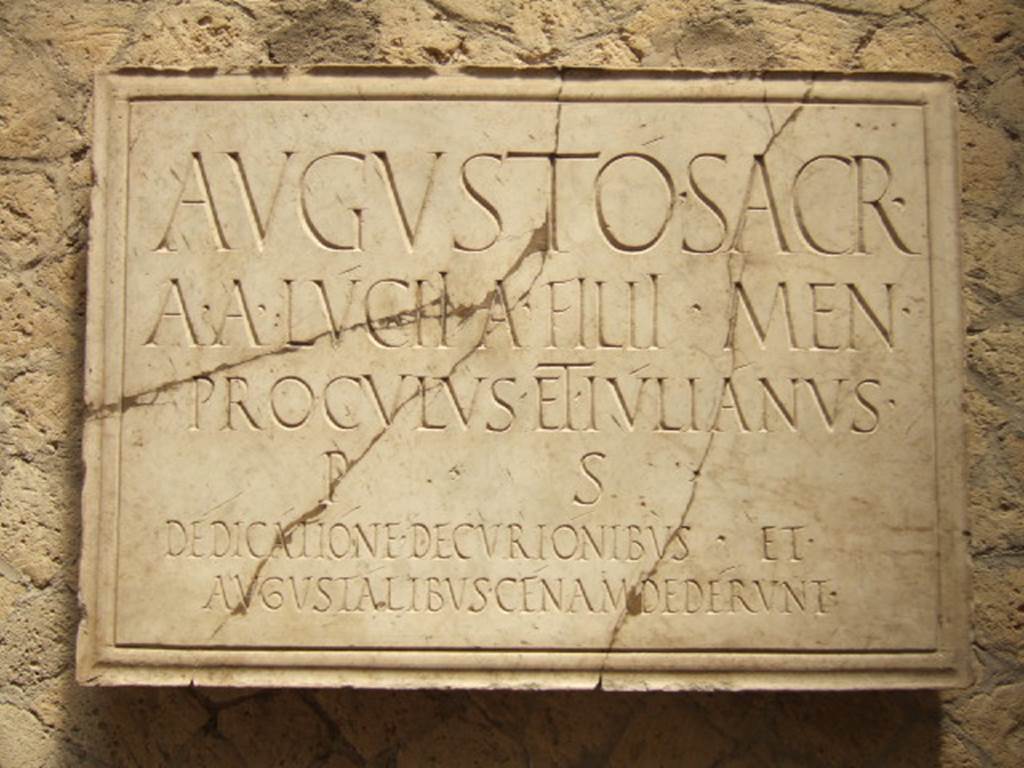

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019.

Plaque dedicated to Augustus.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

According to Camardo and Notomista, this plaque was found on 25th March 1960, and because of its importance, it was decided to leave it in situ.

See Camardo, D, and Notomista, M, ed. (2017). Ercolano: 1927-1961. L’impresa archeologico

di Amedeo Maiuri e l’esperimento della citta museo. Rome, L’Erma di

Bretschneider, (p.245, Scheda 33).

VI.21 Herculaneum, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Plaque dedicated to Augustus. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Plaque dedicated to Augustus. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011. Plaque dedicated to Augustus. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2006. Plaque on north wall.

Deiss wrote that the identification of the Augustales’ structure in Herculaneum is made precise by the dedicatory inscription on the wall.

The inscription fortunately was overlooked by the tunnellers, who stripped all the statuary (probably including Proculus and Julian) and the floors from this hall.

See Deiss, J.J. 1968. Herculaneum: a city returns to the sun. UK, The History Book Club, (p.154)

The inscription reads

AVGVSTO SACR

A A LUCII A FILII

MEN

PROCVLVS ET

IVLIANVS

P S

DEDICATIONE

DECVRIONIBVS ET

AVGVSTALIBVS

CENAM DEDERVNT.

According to Wallace-Hadrill this translates as –

“Sacred to Augustus. Aulus and Aulus Lucius, sons of Aulus, of the tribe Menenia, called Proculus and Julianus, at their own expense, to mark the dedication gave a dinner to the decuriones and the augustales.”

The plaque was found in 1961, according to the archival photograph on page 180.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2011). Herculaneum, Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd., (p.180)

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019. Upper south side.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Upper south side. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2011. Upper south side. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011. Looking south-east from west side. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011. Looking south along upper west side. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. March 2014. Looking towards upper

south-west corner and west side.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019.

Upper west side, with remains of plaster and carbonised beams.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Upper west side, with remains of plaster and carbonised beams. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011.

Looking west towards area with reconstructed modern floor beams of upper floor. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2011.

Looking west towards area with reconstructed modern floor beams of upper floor. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2009. Carbonized beams from upper west floor.

Looking west towards area with reconstructed modern floor beams of upper floor. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2009. Detail of carbonized beams from upper west floor. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2014. Looking towards upper

north-west corner.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. August 2013. Upper north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum. June 2011. Upper north-west corner. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019. Upper north side.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum. May 2009. Detail of carbonized beams from upper north floor. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI.21 Herculaneum, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Looking towards upper north-east corner. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

VI.21, Herculaneum, April 2018. Looking towards upper north-east

corner. Photo courtesy of Ian Lycett-King.

Use is subject to Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License v.4 International.

VI.21, Herculaneum, March 2014. Looking towards upper north-east

corner.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC

Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Looking towards upper north-east corner and east wall. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

VI.21, Herculaneum, March 2014.

Upper north-east corner and east side.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR

VI.21 Herculaneum, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

North-east corner,

detail of carbonised beams. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

VI.21 Herculaneum, March 2019.

Upper east side.

Foto Annette Haug, ERC Grant 681269 DÉCOR.