Ercolano Teatro or Herculaneum theatre.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Alcubierre

1739 plan with full key

Statues which may

have come from the Theatre, also included in the Part above.

Many of the statue said to be from this theatre may in fact have come

from the Basilica Noniana, the Augusteum or vice-versa.

According to Kraus,

“Just which statues adorned the Basilica is difficult to say, since in so

many cases the findings were simply lumped together with those from the

Theatre”.

“Likewise, unknown is the precise disposition of the Equestrian Statue of

Marcus Nonius Balbus, the most respected and influential citizen of

Herculaneum, and the full length figures of his family”.

See Kraus T. and von Matt L., 1975. Pompeii and Herculaneum: Living cities

of the dead. New York: Abrams, (p.120).

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, (inv.6014) in centre, and

white marble statue of Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger), on right.

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological

Museum. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe

Ciaramella.

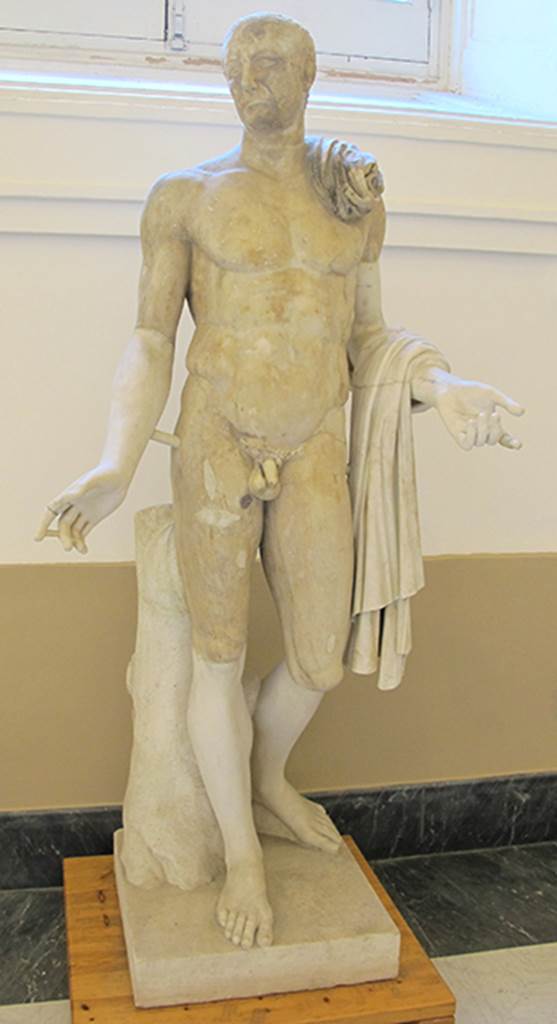

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue interpreted as Mars Ultor known as Pyrrhus (Mars the

Avenger).

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum,

inv.6124.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

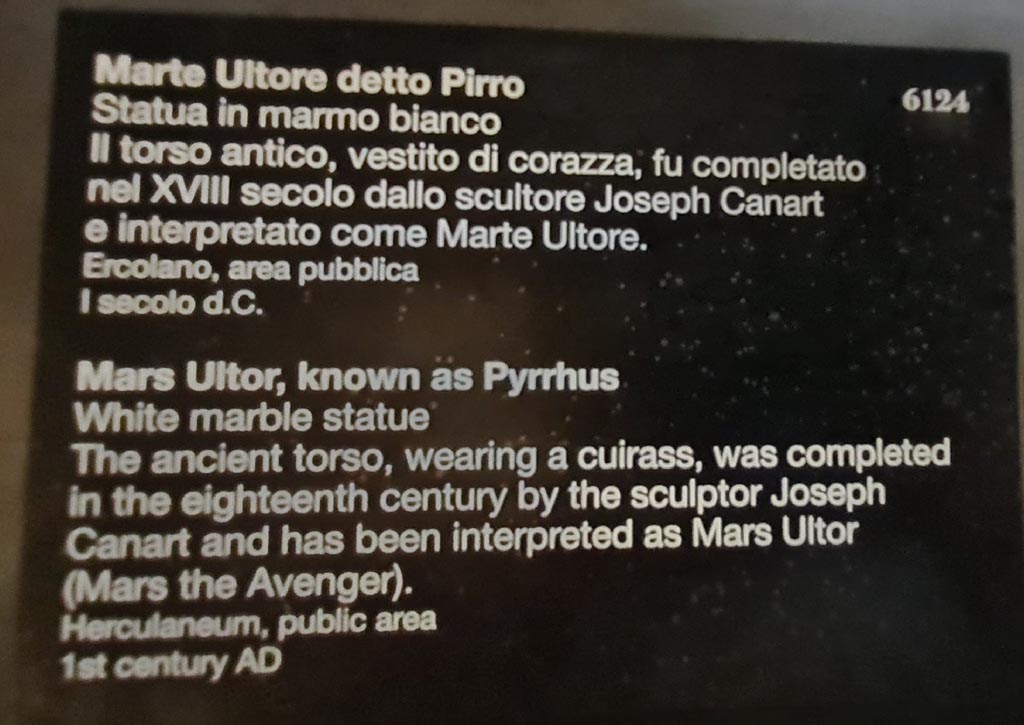

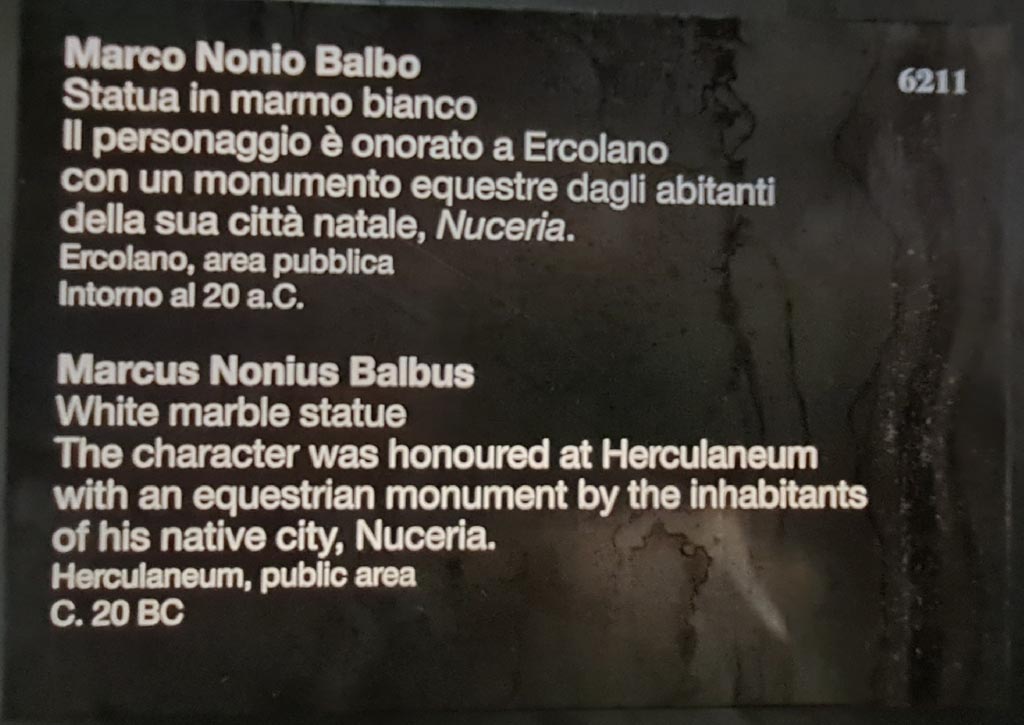

Herculaneum. April 2023. Descriptive card. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe

Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, side view, on display in

“Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum. inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, front view, on display in

“Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, on display in “Campania

Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April

2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, second side view, on display

in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, on display in “Campania

Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

White marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, (inv. 6014), detail of

cloak, shoes and rear of horse. Photo

courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

Rear of white marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, looking towards the

other (second) statue of M.N Balbus at other end of gallery.

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. 6014.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum. April 2023. Descriptive card. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe

Ciaramella.

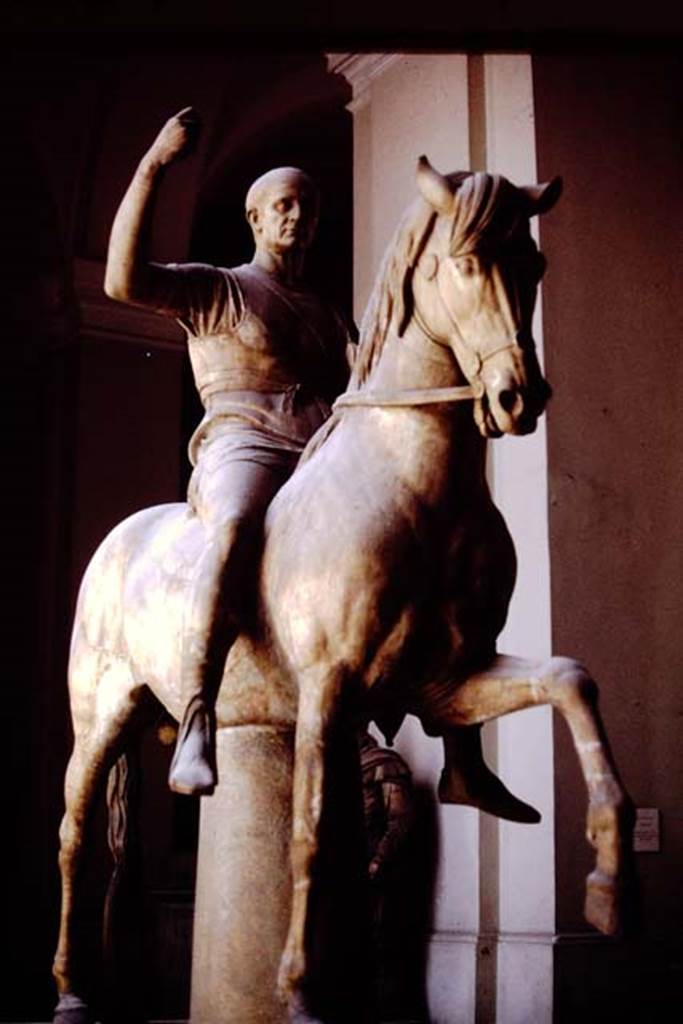

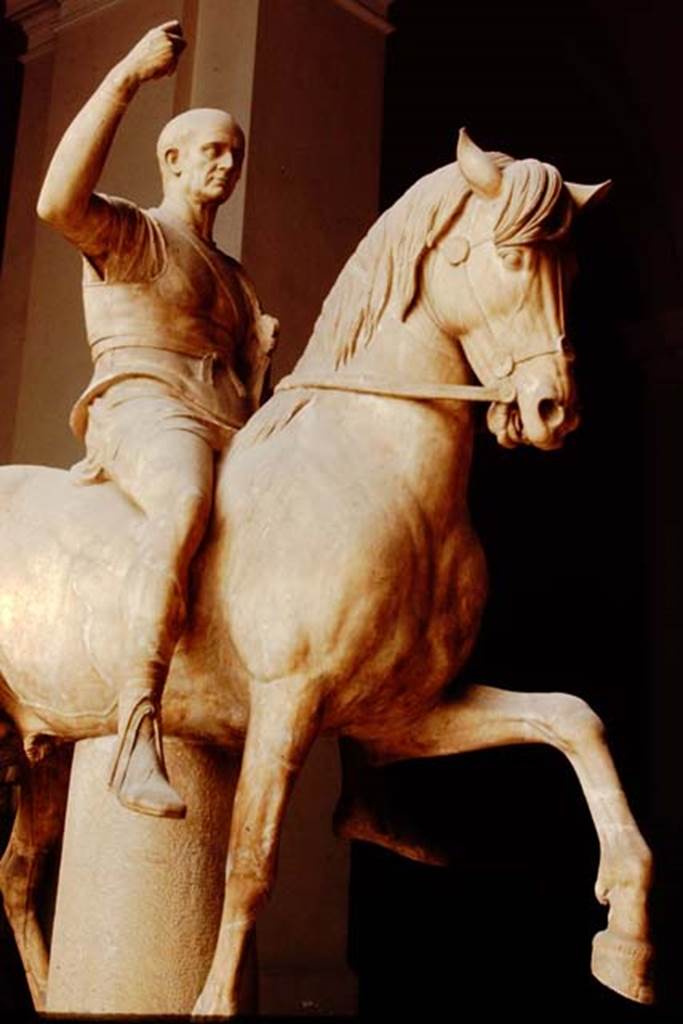

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Equestrian statue of the younger M. Nonius

Balbus found intact in 1746.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6104. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

![Herculaneum Theatre. September 2015. Reproduction equestrian statue of the younger M. Nonius Balbus at Palazzo Reale.

This cast was placed here recently as a reminder of where the original stood in the mid eighteenth century.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6104.

A copy of the original inscription plaque is attached to the front. When first found this identified the statues as M. Nonius Balbus.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio)

Balbo, pr(aetori), pro co(n)s(uli),

Herculanenses. [CIL X 1426]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3731.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image015.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. September

2015. Reproduction equestrian statue of the younger M. Nonius Balbus at Palazzo

Reale.

This cast

was placed here recently as a reminder of where the original stood in the mid

eighteenth century.

Now in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6104.

A copy of

the original inscription plaque is attached to the front. When first found this

identified the statues as M. Nonius Balbus.

![Herculaneum Theatre. Original inscription plaque is attached to the front of statue base of 6104.

When first found this identified the statues as M. Nonius Balbus.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio)

Balbo, pr(aetori), pro co(n)s(uli),

Herculanenses. [CIL X 1426]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3731.

Photo courtesy of Jørgen Christian Meyer.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image017.jpg)

Herculaneum

Theatre. Original inscription plaque is attached to the front of statue base of

6104.

When first

found this identified the statues as M. Nonius Balbus.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio)

Balbo, pr(aetori), pro co(n)s(uli),

Herculanenses. [CIL X 1426]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3731. Photo

courtesy of Jørgen Christian Meyer.

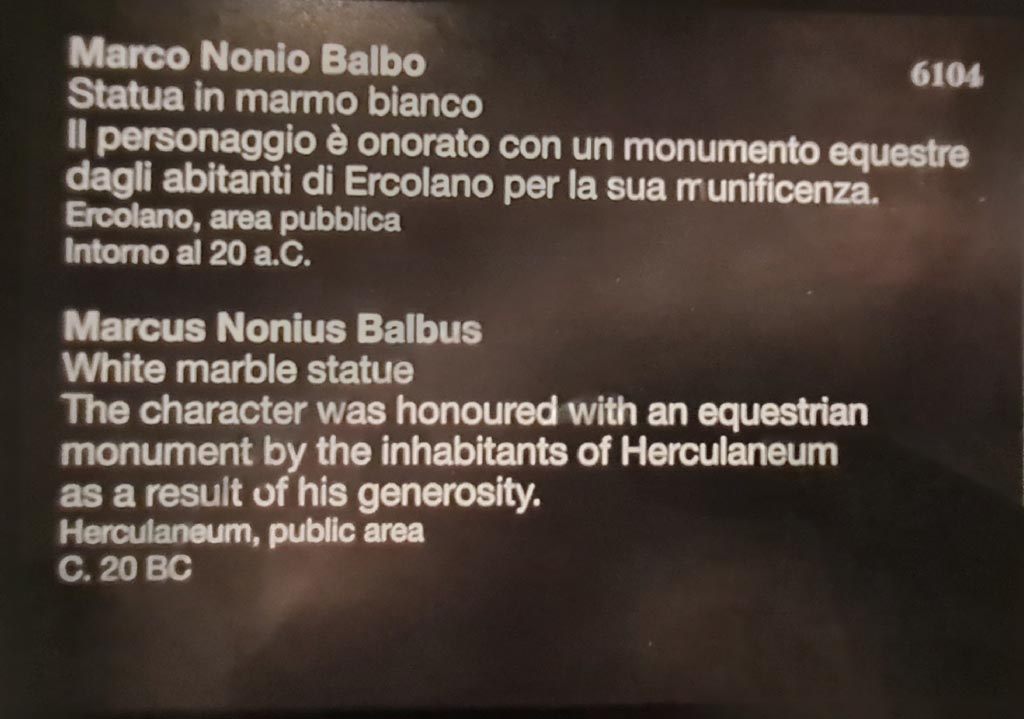

Herculaneum. 1782. Two statues of Nonius Balbus, now in Naples Museum.

This drawing, from St Non, shows the

elder/father statue with a bearded head.

According

to the information board in Palazzo Reale in 2015, this was inspired by the

most famous equestrian statue of antiquity, the Marcus Aurelius in Piazza del

Campidoglio in Rome, a purely graphical restoration giving a different

interpretation from that of Canart.

See Saint Non J., 1782. Voyage

Pittoresque ou Description Des Royaumes de Naples et de Sicile : Tome

1 Partie 2, Chap. VIII, p. 36.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

Second white marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, at other end of

gallery.

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum,

inv. 6211.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum. April 2023. Descriptive card. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe

Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

Second white marble statue of Marcus Nonius Balbus, inv. 6211.

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum, public area. April 2023.

Rear of horse belonging to second white marble statue of Marcus Nonius

Balbus, inv. 6211.

On display in “Campania Romana” gallery of Naples Archaeological Museum.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

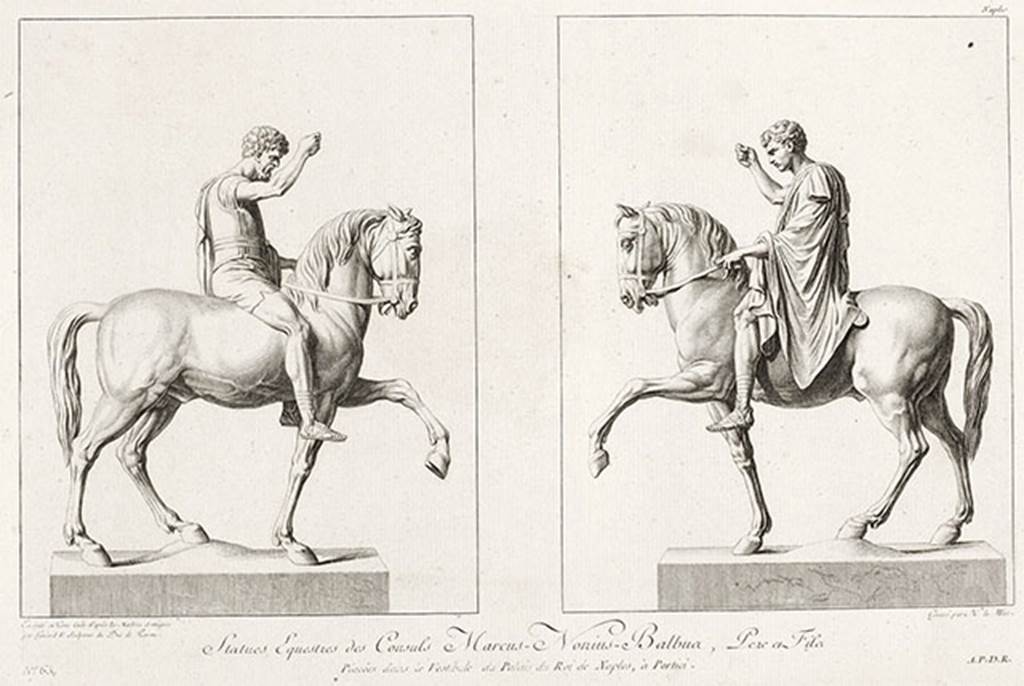

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Equestrian statue of the elder M. Nonius

Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6211. Photo

courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

According to the information board in the Palazzo Reale at Portici in

2015, the statue was found in 1746 and was in pieces and headless.

The sculpture was believed to depict Balbus the Younger’s father.

Hence, during restoration, Canart made a head for it after a portrait

certainly showing Balbus senior, in compliance with the principles of

Classicism, which called for full restoration of mutilated sculptures.

Actually, the two statues are believed to portray the same individual,

being honoured respectively by the towns of Nuceria and Herculaneum.

Herculaneum Theatre. 1978. Statue of M. Nonius Balbus,

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6211.

This statue is often identified as the father of M. Nonius Balbus.

The two statues on horseback may be of the same M. Nonius Balbus but portraying

earlier and later stages in his life.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii

and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, (p.186-191, F94-105)

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J78f0441

According to Wallace-Hadrill, this statue is often thought of as being

from the so-called Basilica but in fact was from outside the theatre.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2011. Herculaneum,

Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd, (p.192).

According to the information board in the Palazzo Reale at Portici in

2015, the two statues are believed to portray the same individual, being

honoured respectively, by the towns of Nuceria and Herculaneum.

Herculaneum Theatre. 1968.

Statue of the elder Nonius Balbus, now in the Naples Museum. Photo by

Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J68f0839

The left

hands hold the reins. On the third finger of each left hand is a large signet

ring.

The right

hands are raised aloft in gestures of imperial command. The Proconsul’s

hairline is receding.

The son’s

abundant hair is cut short and combed forward in the Roman fashion.

The

Proconsul’s face conveys all the haughty authority of a high Roman official who

is an overseas administrator.

The son’s

face conveys uncertainty, distaste for an assumed role, and resignation.

The

Proconsul’s tight lips are curt with self-assurance and executive drive.

The son

frowns, and the full lips almost tremble with petulance.

If the

sculpture has told the truth, here indeed was a son in severe conflict with the

father or other members of the family.”

See Deiss,

J.J. (1968). Herculaneum, a city returns

to the sun. UK, The History Book Club, (p.143-4).

According to Wallace-Hadrill, these statues are often thought of as being

from the so-called Basilica but in fact were from outside the theatre.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2011. Herculaneum,

Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd, (p.192).

![Herculaneum Theatre. 1978. Statue of younger Nonius Balbus, now in Naples Museum.

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial License v.4. See Licence and use details.

J78f0437

According to Kraus, “The head of Balbus [the younger] is a modern copy made by the sculptor Angelo Brunelli (1740-1806) after the original was destroyed in 1799 by a cannonball fired by the revolutionaries attacking the royal villa and museum in Portici.”

See Kraus T. and von Matt L., 1975. Pompeii and Herculaneum: Living cities of the dead. New York: Abrams, (p.125).

According to Wallace-Hadrill, Marcus Nonius Balbus was one of the leading citizens and benefactors of Herculaneum.

He became a praetor in Rome, and the governor (proconsul) of Crete and Cyrene.

In the Basilica Noniana, his portrait in the toga of a citizen, is accompanied by that of his father, with the same name, his mother Viciria, probably his wife Volasennia, and possibly his daughters.

The impression of his face was left in the tufa at the Theatre, from his statue in heroic nudity.

We see statues of him together with his father, both on horseback from a public square outside the Theatre, with an inscription recalling his benefactions to the town.

Finally, his statue can be found on the terrace by the Suburban Baths, in the armour of a Roman commander.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2011. Herculaneum, Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd, (p.130-133 and p. 192).](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image031.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. 1978.

Statue of younger Nonius Balbus, now in Naples Museum. Photo by Stanley

A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J78f0437

According to Kraus, “The head of Balbus [the younger] is a modern copy made by the sculptor Angelo Brunelli

(1740-1806) after the original was destroyed in 1799 by a cannonball fired by

the revolutionaries attacking the royal villa and museum in Portici.”

See Kraus T. and von Matt L., 1975. Pompeii and Herculaneum: Living cities

of the dead. New York: Abrams, (p.125).

According to Wallace-Hadrill, Marcus Nonius Balbus was one of the leading

citizens and benefactors of Herculaneum.

He became a praetor in Rome, and the governor (proconsul) of Crete and

Cyrene.

In the Basilica Noniana, his portrait in the toga of a citizen, is

accompanied by that of his father, with the same name, his mother Viciria,

probably his wife Volasennia, and possibly his daughters.

The impression of his face was left in the tufa at the Theatre, from his

statue in heroic nudity.

We see statues of him together with his father, both on horseback from a

public square outside the Theatre, with an inscription recalling his

benefactions to the town.

Finally, his statue can be found on the terrace by the Suburban Baths, in

the armour of a Roman commander.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2011. Herculaneum,

Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd, (p.130-133 and p. 192).

Herculaneum Theatre. 1968.

Statue of Nonius Balbus, now in Naples Museum. Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J68f1413

According to Wallace-Hadrill, this statue is often thought of as being

from the so-called Basilica but in fact was from outside the theatre.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2011. Herculaneum,

Past and Future. London, Frances Lincoln Ltd, (p.192).

Herculaneum Theatre. Statue known as the large Herculaneum woman type.

Height 203cm.

One of three statues from the theatre, taken by D’Elboeuf and given to

Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna.

© Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden, Foto: Ingrid Geske. Inventory number Hm 326.

In 1711 workers digging a well in the small town of Resina, Italy, found

three mostly intact life-size marble statues of draped women.

Heralding the discovery of ancient Herculaneum, the sculptures are known

today as the Large and Small Herculaneum Women.

When they were discovered, the Herculaneum Women were hoisted through a

well shaft that led down to the remains of a Roman theatre buried 75 feet below

the street level of modern Ercolano.

They probably once decorated the stage's impressive double-tiered façade,

along with other sculptures of mythological and historical figures.

In Roman cities, theatres were a common place for the display of

honorific statues of patrons and benefactors of the community.

The Herculaneum Women may thus have represented members of the local

elite.

The Herculaneum Women were the first significant finds at ancient

Herculaneum, and they are among the best preserved of all the sculptures found

there.

The Herculaneum Women are Roman versions of sculptural types deriving from

Greek art.

They have idealized facial features, wear elegant, enveloping drapery,

and share the same distinctive hairstyle, the so-called melon coiffure, which

became fashionable in Greece after 350 B.C., when the models for the

Herculaneum Women were created.

The Large Herculaneum Woman represents a matron and has part of her mantle

pulled up over her head, signifying piety.

The Small Herculaneum Woman depicts a younger woman pulling the end of

her mantle up over her shoulder in a gesture of modesty.

The third Herculaneum Woman was missing its head when it was found.

Her portrait head, probably with individual features, was carved

separately for insertion into the neck cavity.

These body types were widely used for portraits of Roman women, but the

two types have rarely been found together.

According to Vorster, the stylistic analysis of the Dresden statues and

their consideration in the context of the other sculptural finds from the same

site lead rather to the conclusion that the three statues must have come to the

Herculaneum Theatre at different times. The statue of the small Herculaneum

Woman, Hm 327, may be considered not just one of the oldest sculptures of the

Herculaneum Theatre but also one of the earliest examples of a female honorific

statue erected in a public place in Italy.

See The Getty - Herculaneum Women - 2007 Exhibition

See The Getty - Herculaneum Women - Learn more

See Sybel L. Von, 1888. Weltgeschichte der Kunst bis zur Erbauung der Sophienkirche, p.

254, fig. 207.

See Vorster C.,

in Daehner J., ed., 2007. The

Herculaneum Women: History, Context, Identities, Getty Publications: Los Angeles, p.

83.

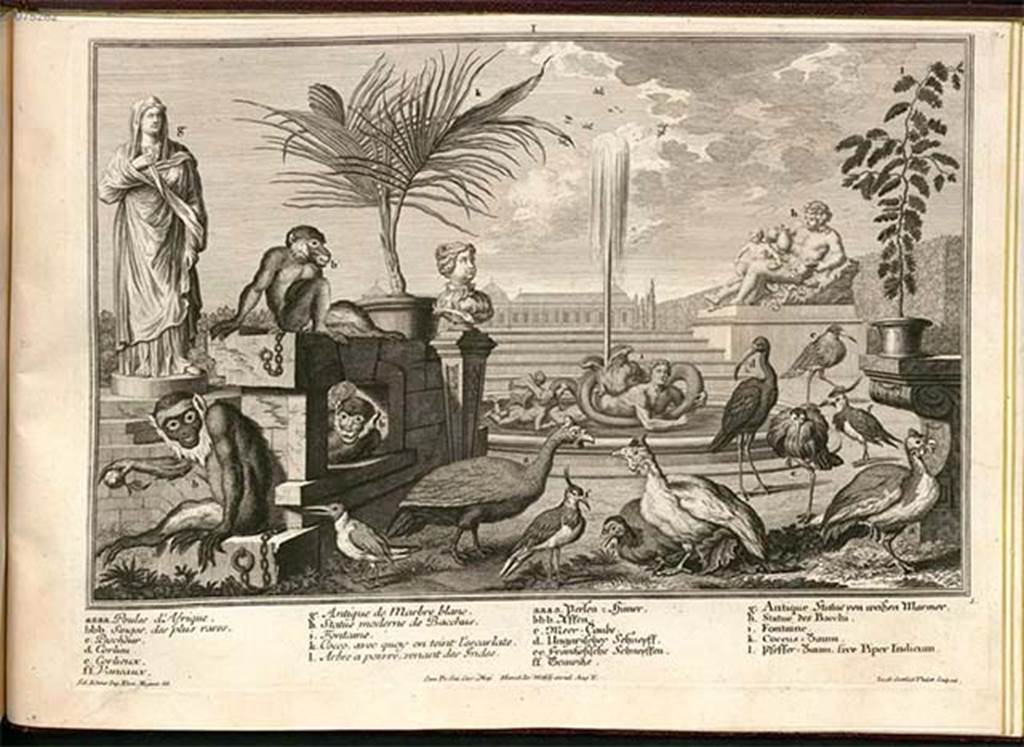

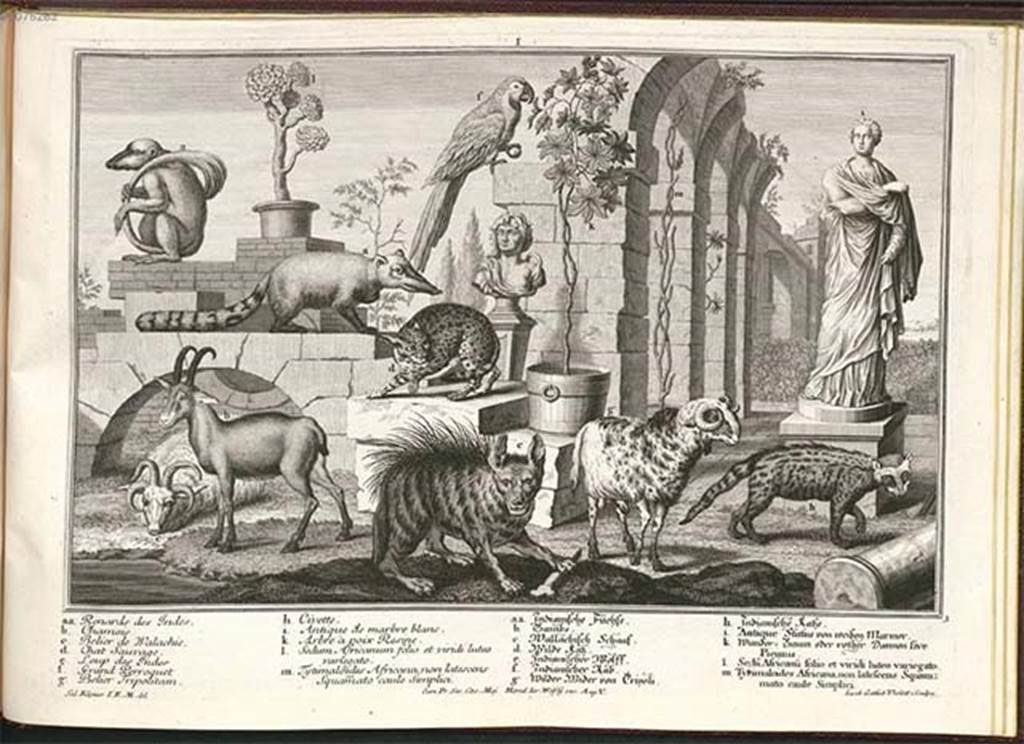

Herculaneum Theatre. 1734 drawing showing a Herculaneum woman statue (g)

in the menagerie of Prince Eugene de Savoye.

Prince d'Elboeuf, whose workmen discovered the Herculaneum Women,

presented the sculptures as a gift to Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna.

The earliest illustrations of the Herculaneum Women, shown here, depict

them among the exotic animals Eugene kept at his Belvedere Gardens.

After Eugene's death in 1736 Augustus III, elector of Saxony and King of

Poland, purchased the statues to complement the royal antiquities collection in

Dresden.

Housed in the Albertinum since the end of the 19th century, the

Herculaneum Women are centrepieces of the Dresden antiquities collection.

See Kleiner, Salomon, 1734. Représentation Des Animaux de la Ménagerie de S. A. S. Monseigneur le

Prince Eugene François de Savoye et de Piémont. Augsbourg:

Wolff, p. 3.

Picture courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Usable subject to

licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Herculaneum Theatre. Statue known as the small Herculaneum woman type.

Height 179cm.

Second of three statues from the theatre, taken by D’Elboeuf and given to

Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna.

© Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden, Foto: Ingrid Geske. Inventory number Hm 327.

According to Vorster, this statue may be one of the earliest examples of

a female honorific statue erected in a public place in Italy.

See Vorster C., in Daehner J., ed., 2007. The

Herculaneum Women: History, Context, Identities, Getty

Publications: Los Angeles, p. 83.

Herculaneum Theatre. 1734 drawing showing a small Herculaneum woman

statue (i) in the menagerie of Prince Eugene de Savoye.

See Kleiner, Salomon, 1734. Représentation Des Animaux de la Ménagerie de S. A. S. Monseigneur le

Prince Eugene François de Savoye et de Piémont. Augsbourg:

Wolff, p. 7.

Picture courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Usable subject to

licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Herculaneum Theatre. Statue known as the small Herculaneum woman type.

Height 180cm.

One of three statues from the theatre, taken by D’Elboeuf and given to

Prince Eugene of Savoy in Vienna.

© Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden, Foto: Ingrid Geske.

Inventory number Hm 328.

This third statue was without a head when found.

It shows how the statue type would have had a portrait head attached.

The head, probably with individual features, was carved separately for

insertion into the neck cavity.

The Herculaneum Women are the most prevalent images of the draped female

form in the classical world.

Their elegant, enveloping drapery and composed stance represented

feminine virtues of beauty, grace, and decorum in both Greek and Roman

societies.

More than 180 examples of the large statue type and over 160 of the small

statue type are known, along with dozens of variants and reliefs on tombstones

and sarcophagi.

The majority of the figures are combined with individualized portraits.

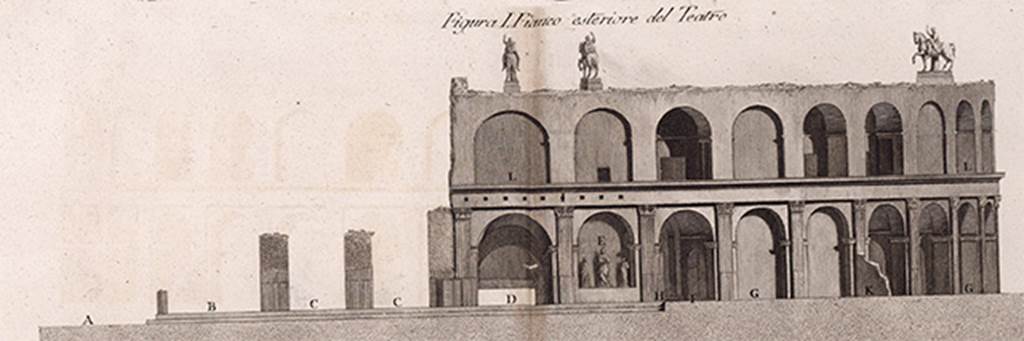

Herculaneum Theatre. 1783 engraving by F. Piranesi of the flank of the

theatre.

According to Piranesi, D is the entrance to the orchestra and at E were

three statues.

In the centre was one with the inscription ..CIRIAE A M F ACARD MATRIS

BALBI D D.

To the right was a statue with the inscription M NONIO BALBO PAT D D D.

Under the other statue was the inscription M NONIO M F BALBO PR PRO COS

ERCVLANENSES.

See Piranesi, F, 1783. Teatro di Ercolano, Tav. V Fig. 1.

![Herculaneum Theatre, 1975. Marble statue of Viciria, mother of Nonius Balbus, “found in the Basilica”.

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial License v.4. See Licence and use details.

J75f0575

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory number 6168.

The inscription under the statue read

Viciriae A(uli) f(iliae) Archaid(i) / matri Balbi / d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1440]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory number 6872.

According to Cooley the following inscription was found in the Basilica Noniana with the female statue –

“To Viciria Archais, daughter of Aulus, mother of Balbus, by decree of the town councillors.” (CIL X 1440)

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, (p.190, F101).

According to Piranesi it was found in the theatre.

See Piranesi, F, 1783. Teatro di Ercolano, Tav V Fig 1.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image047.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre, 1975.

Marble statue of Viciria, mother of Nonius Balbus, “found in the

Basilica”. Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J75f0575

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum,

inventory number 6168.

The inscription under the statue read

Viciriae A(uli) f(iliae) Archaid(i) / matri Balbi / d(ecreto)

d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1440]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory number 6872.

According to Cooley the following inscription was found in the Basilica

Noniana with the female statue –

“To Viciria Archais, daughter of Aulus, mother of Balbus, by decree of

the town councillors.” (CIL X 1440)

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii

and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, (p.190, F101).

According to Piranesi it was found in the theatre.

See Piranesi, F, 1783. Teatro di Ercolano, Tav V Fig 1.

![Herculaneum Theatre, 1976. Perhaps M. Nonius Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6246.

This statue is associated with the inscription cil x 1439.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

Patri

d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1439]](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image049.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre, 1976. Perhaps M. Nonius Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6246.

This statue is associated with the inscription cil x 1439.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

Patri

d(ecreto)

d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1439]

Herculaneum

Theatre. Statue base inscription associated with statue 6246.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo / patri / d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1439]

Now in

Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory number 6871.

Photo

courtesy of Epigraphic Database Heidelberg (http://edh-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de).

Use subject

to licence CC BY-SA 4.0

According to Cooley and Cooley this reads as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, father, by decree of the town

councillors.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A

Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F100, p. 190.

![Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Statue of M. Nonius Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6167.

This statue was associated with the base inscription CIL X, 1428.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

pr(aetori) proco(n)s(uli)

d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1428]

According to Cooley and Cooley this reads as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, by decree of the town councillors.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F99, p. 190.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6873.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image053.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Statue of M. Nonius Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6167.

This statue was associated with the

base inscription CIL X, 1428.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

pr(aetori) proco(n)s(uli)

d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X

1428]

According

to Cooley and Cooley this reads as

To Marcus

Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, by decree of the town

councillors.

See Cooley,

A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London:

Routledge, F99, p. 190.

Now in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6873.

Herculaneum

Theatre. Inscription plaque to M. Nonio Balbo.

[M(arco)] Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) / [B]albo pr(aetori) pro[c]o(n)s(uli) /

[G]ortyniei ae[re [CIL X 1434]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3736. Photo

courtesy of Jørgen Christian Meyer.

According

to Cooley and Cooley, this reads as

To Marcus

Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, the people of Gortyn, having

made a collection.

Inscriptions

show that Nonius Balbus was honoured after his governorship of Crete by the

towns of Gortyn and Cnossus [CIL X 1433] as well as by the Cretans as a whole

[CIL X 1431-32]

See Cooley,

A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London:

Routledge, F98, p. 189.

Herculaneum

Theatre.

Heroic nude

statue in white marble with portrait head of M. Nonius Balbus (the so-called

Maximinus).

Now in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6102.

Photo

courtesy Sailko via Wikimedia Commons, licence CC BY-SA 3.0.

Herculaneum. Daughter of M. Nonius Balbus.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum.

Inventory number 6248.

Herculaneum, 1975.

Perhaps one of the daughters of Nonius Balbus, found in the Basilica.

Photo by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J75f0573

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6248.

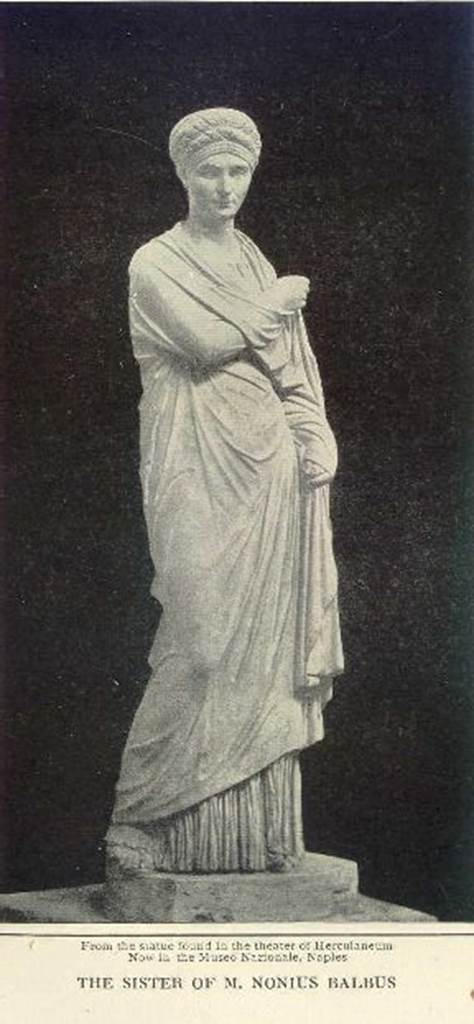

Herculaneum, 1976. Perhaps one of the daughters of Nonius Balbus, found

in the Basilica.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 6244.

Old photo titled

“From the statue found in the theatre of Herculaneum. Now in the Museo

Nazionale Naples. The Sister of M. Nonius Balbus”,

Herculaneum Theatre. Statue of Marcus Calatorius Quarto.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5597.

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Statue of M. Calatorius Quarto.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5597. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

The inscription on the related plaque honouring Calatorius Quarto is

recorded in CIL X 1447.

![Herculaneum Theatre. Plaque relating to statue of M. Calatorius Quarto.

The inscription honouring Calatorius Quarto is recorded in CIL X 1447.

M(arco) Calatorio M(arci) [f(ilio)]

Quartion[i]

municipes et in[colae]

aere conlato [CIL X 1447]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Marcus Calatorius Quarto, son of Marcus. The townsfolk and residents (set this up) by public subscription.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D67b, p. 94.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3730.

See plaque on EPIGRAPHIC DATABASE ROMA](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image070.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. Plaque relating to statue of M. Calatorius Quarto.

The inscription honouring Calatorius Quarto is recorded in CIL X 1447.

M(arco) Calatorio M(arci) [f(ilio)]

Quartion[i]

municipes et in[colae]

aere conlato

[CIL X 1447]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Marcus Calatorius Quarto, son of Marcus. The townsfolk and residents

(set this up) by public subscription.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A

Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D67b, p. 94.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3730.

See plaque on EPIGRAPHIC DATABASE ROMA

Herculaneum Theatre or Augusteum. Antonia Minore.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5599.

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Statue

of Antonia Minore.

Now in

Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5599. Photo

courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Detail of statue of Antonia Minore.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5599. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

Herculaneum Theatre. May 2010. Detail of hand with ring on statue of

Antonia Minore.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5599. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

Herculaneum Theatre. Statue of Lucius Mammius Maximus freedman.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5591.

Probably found with the statue was the marble plaque with the inscription

L(ucio) Mammio Maximo / Augustali / municipes et

incolae / aere conlato

According to Cooley and Cooley, this read as

To Lucius Mammius Maximus, Augustalis. The townsfolk and residents (set

this up) by public subscription.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A

Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D63, p. 93.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3748.

See plaque on EPIGRAPHIC DATABASE ROMA

![Herculaneum Theatre. Inscription to Lucius Annius Mammianus Rufus freedman.

He is commemorated in a large inscription, 4.15m wide, one of several inscriptions commemorating the funding for the theatre by the local magistrate and (in smaller lettering) the contribution of the architect to its design.

L(ucius) Annius L(uci) f(ilius) Mammianus Rufus IIvir quinq(uennalis) theatr(um) orch(estram) s(ua) p(ecunia)

P(ublius) N(umisius) P(ubli) f(ilius) arc[hi]te[ctus] [CIL X 1443]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this read as

Lucius Annius Mammianus Rufus, son of Lucius, quinquennial duumvir, built the theatre and orchestra at his own expense. Publius Numisius, son of Publius, architect.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D63, p. 93.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3742.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image082.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. Inscription to Lucius Annius Mammianus Rufus freedman.

He is commemorated in a large inscription, 4.15m wide, one of several

inscriptions commemorating the funding for the theatre by the local magistrate

and (in smaller lettering) the contribution of the architect to its design.

L(ucius) Annius L(uci) f(ilius) Mammianus Rufus

IIvir quinq(uennalis) theatr(um) orch(estram) s(ua) p(ecunia)

P(ublius) N(umisius) P(ubli) f(ilius)

arc[hi]te[ctus] [CIL X 1443]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this read as

Lucius Annius Mammianus Rufus, son of Lucius, quinquennial duumvir, built

the theatre and orchestra at his own expense. Publius Numisius, son of Publius,

architect.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A

Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D63, p. 93.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3742.

Herculaneum Theatre. Agrippina Minor.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5612.

Herculaneum Theatre. Livia.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5589.

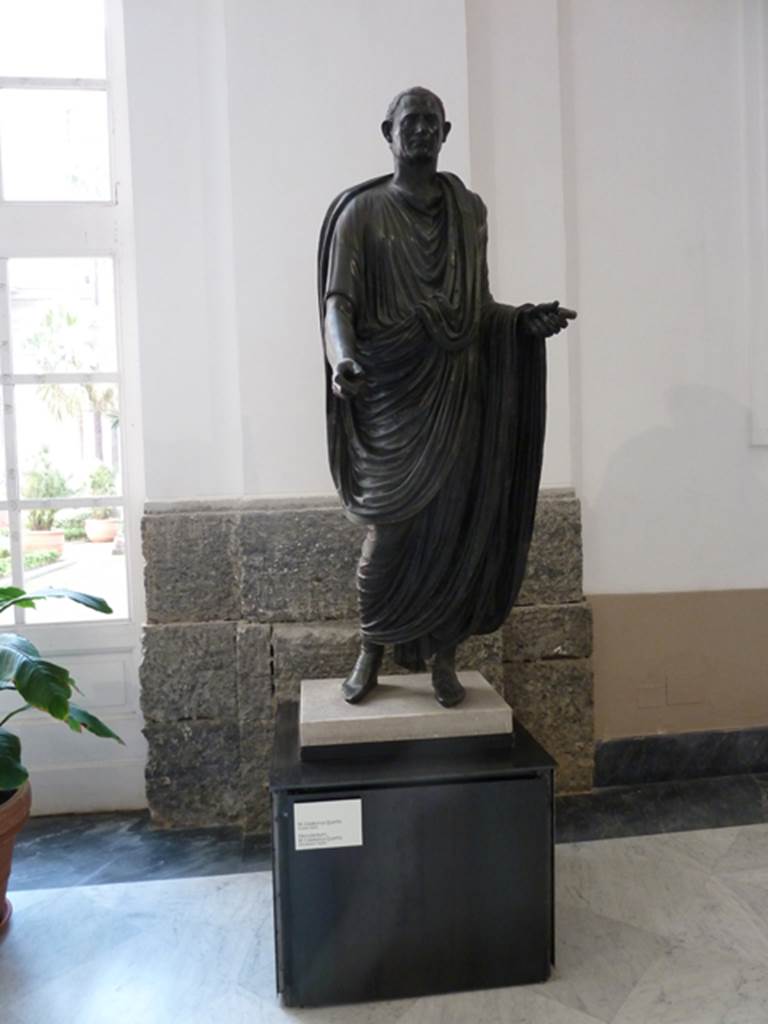

Herculaneum Theatre, 1968. Photo

by Stanley A. Jashemski.

Statue of a Magistrate. Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory

number 6234.

Source: The Wilhelmina and Stanley A. Jashemski archive in the University

of Maryland Library, Special Collections (See

collection page) and made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non

Commercial License v.4. See Licence and

use details.

J68f1414

Herculaneum Theatre. Tiberius.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 5615.

Herculaneum Theatre.

Two statues possibly from the Theatre now on the staircase at the Royal

Palace of Portici.

Photo courtesy of Davide Peluso.

Herculaneum Theatre.

Statue possibly from the Theatre now outside at the Royal Palace of

Portici.

Photo courtesy of Davide Peluso.

Herculaneum Theatre.

Statue possibly from the Theatre in niche outside at the Royal Palace of

Portici.

Photo courtesy of Davide Peluso.

Herculaneum Theatre.

Statue possibly from the Theatre, now in niche outside at the Royal

Palace of Portici.

Photo courtesy of Davide Peluso.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Alcubierre 1739 plan with full key

![Herculaneum Theatre. Statue base inscription associated with statue 6246.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo / patri / d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) [CIL X 1439]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum, inventory number 6871.

Photo courtesy of Epigraphic Database Heidelberg (http://edh-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de).

Use subject to licence CC BY-SA 4.0

According to Cooley and Cooley this reads as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, father, by decree of the town councillors.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F100, p. 190.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image051.jpg)

![Herculaneum Theatre. Inscription plaque to M. Nonio Balbo.

[M(arco)] Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) / [B]albo pr(aetori) pro[c]o(n)s(uli) / [G]ortyniei ae[re [CIL X 1434]

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 3736.

Photo courtesy of Jørgen Christian Meyer.

According to Cooley and Cooley, this reads as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, the people of Gortyn, having made a collection.

Inscriptions show that Nonius Balbus was honoured after his governorship of Crete by the towns of Gortyn and Cnossus [CIL X 1433] as well as by the Cretans as a whole [CIL X 1431-32]

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, F98, p. 189.](Herculaneum%20Teatro%20p3_files/image055.jpg)