Ercolano Teatro or Herculaneum theatre.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Alcubierre 1739 plan with full key

Herculaneum Theatre, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Entrance to ancient Theatre on Corso Resina. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2015. Entrance to ancient Theatre on Corso Resina. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

Herculaneum, July

2009. Looking south along Vico di Mare. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2015. Entrance to ancient Theatre. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2015. Entrance to ancient Theatre. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

According to Maiuri –

“The entrance to the Theatre may be reached by walking up the populous and popular Vico a Mare to the Corso.

The upper entrance lies amidst the houses of modern Resina built over the cavea; an inscription of 1865 records the last improvements made upon it”. (see Maiuri, p. 73)

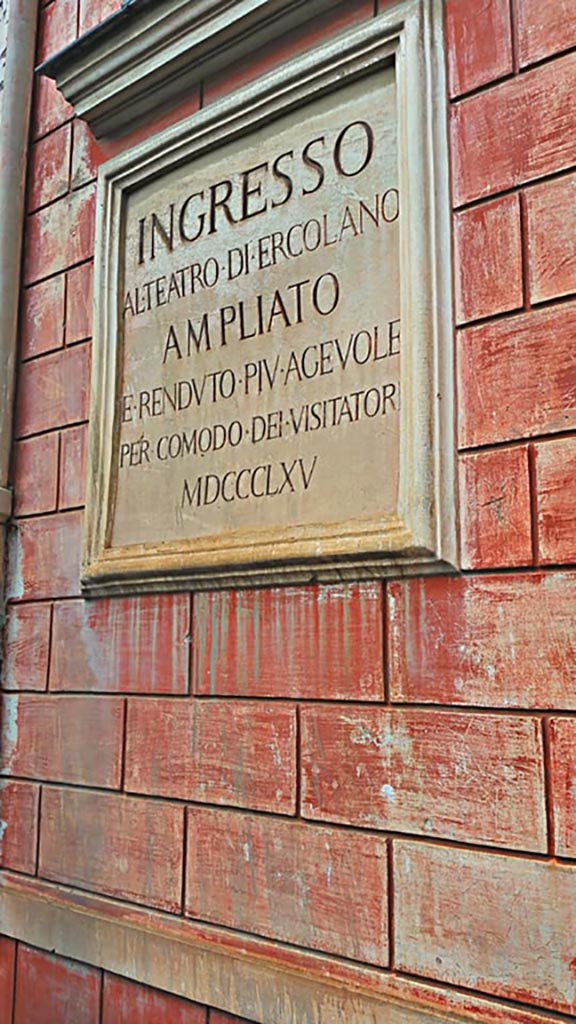

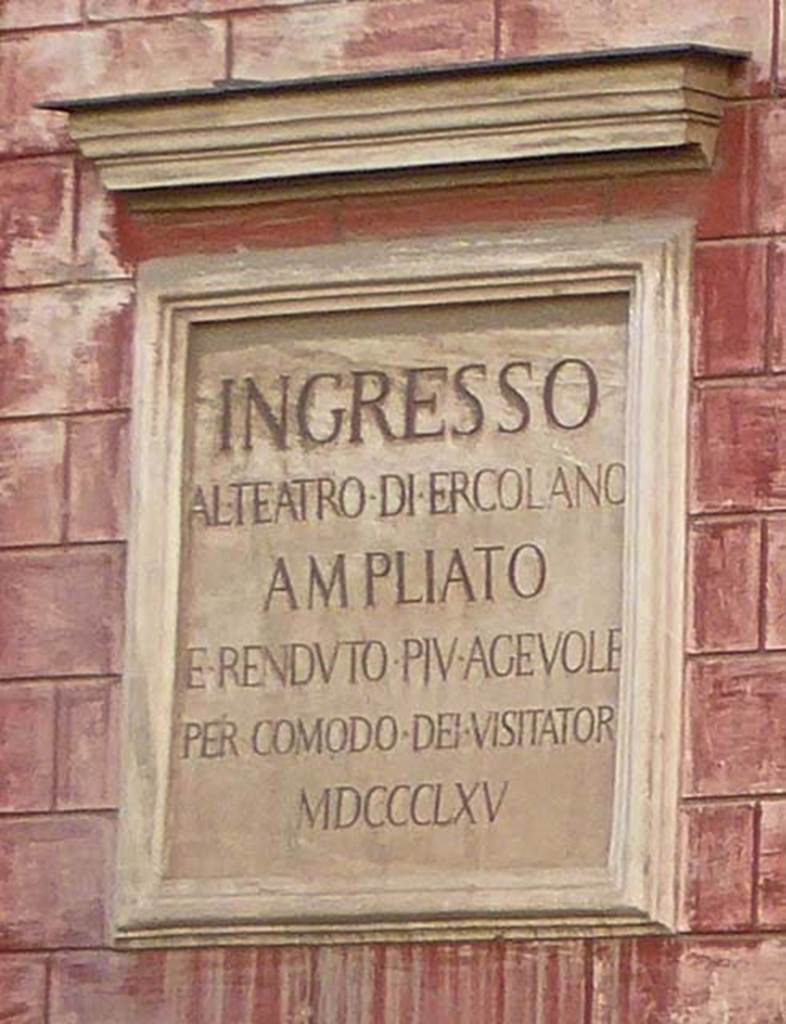

Herculaneum Theatre, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Plaque on entrance to ancient Theatre. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2015. Plaque on entrance to

ancient Theatre. Photo courtesy of

Michael Binns.

“Ingresso al

Teatro di Ercolano ampliato e renduto più agevole per comodo dei visitatori MDCCCLXV.”

Entrance to the Herculaneum Theatre, enlarged and made easier for visitors' convenience 1865.

Herculaneum Theatre, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Preparing for the underground tour – hard hats, torch-lights and warm clothing. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

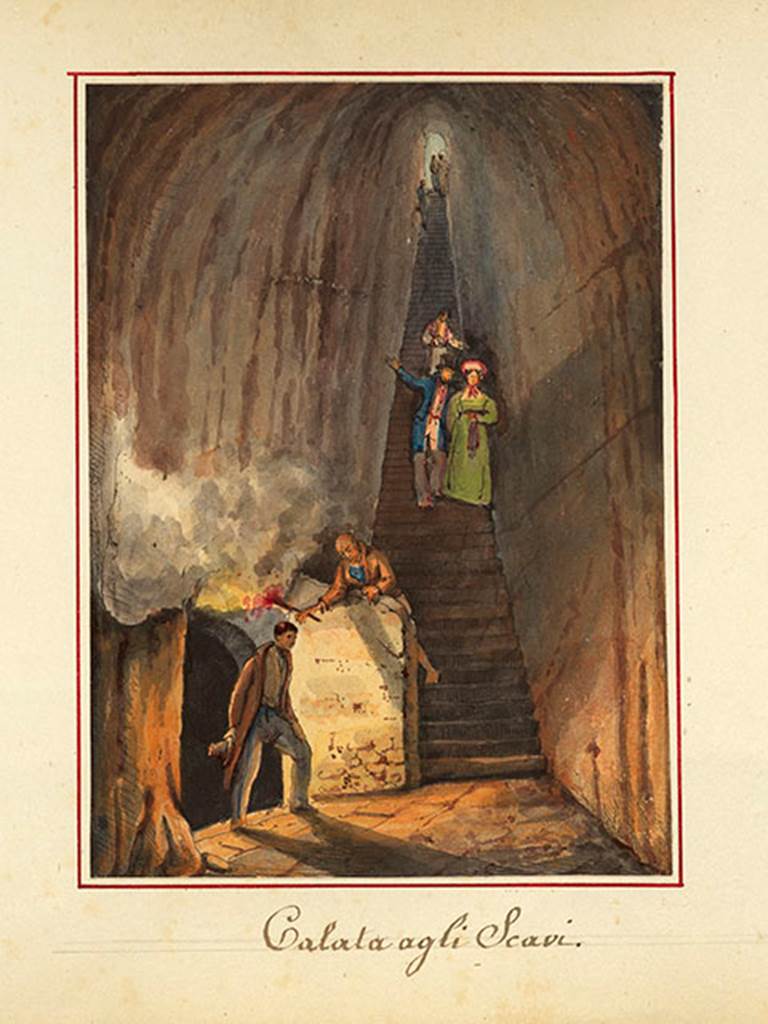

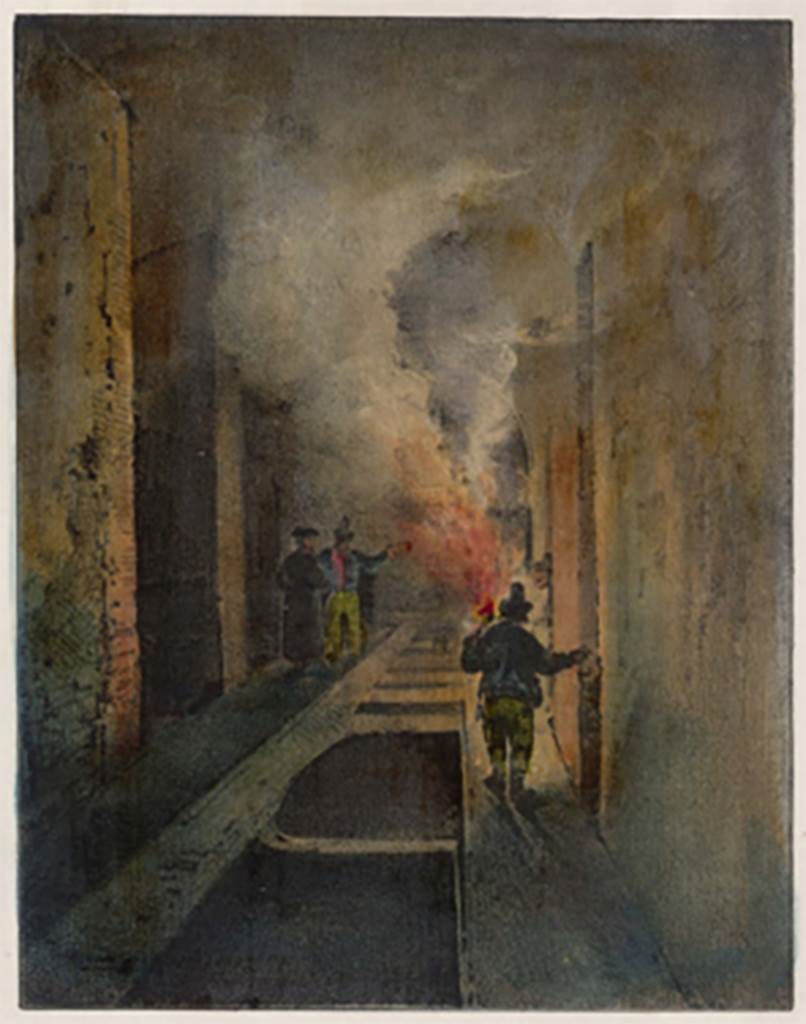

Herculaneum

Theatre, c.1840? Painting entitled “Calata

agli Scavi” (descent into the excavations).

Artist unknown.

Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Herculaneum Theatre.

October 2023.

Steps down to the

theatre. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023.

Original steps up between the rows of

seats in the theatre. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023.

Detail of original steps up from the

theatre. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre.

October 2023. Looking down access shaft onto seating and steps. Photo courtesy

of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009.

The eighteenth-century

access shaft to the theatre. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009.

The eighteenth-century

access shaft to the theatre. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

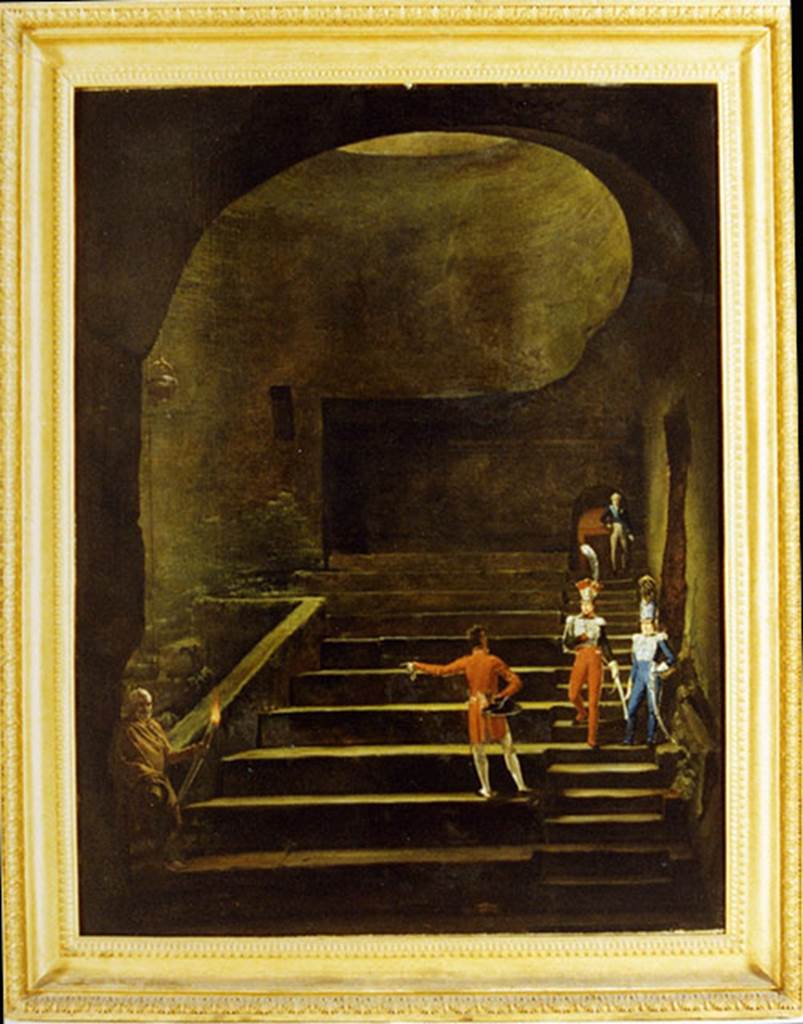

“From the lower

vestibule a flight of 72 steps cut into the tufa bank leads down to the upper

part of the theatre (summa cavea), recognizable

from the double flights of steps that descend to the great circular ambulacrum

between the summa and the media cavea; the latter is traversable

from one extremity to the other, where there are stairs leading down to the

level of the orchestra”…….

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum, (p.73)

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009. Tunnel with electricity. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

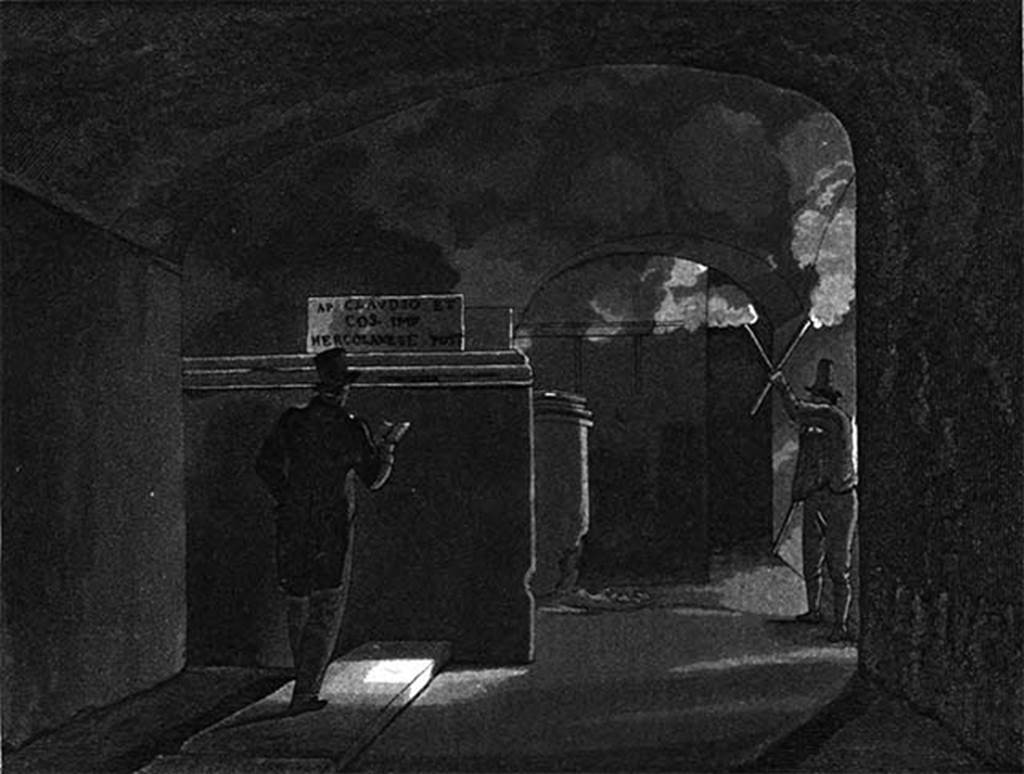

According to Deiss

–

“Today, the well of

Prince d’Elboeuf and Alcubierre’s tunnels, crisscrossing the Theatre, remain

much as they were when the explorations were finally abandoned. From them the

present visitor derives the most vivid impressions of the conditions under

which the Neapolitan cavamonti worked

so deep underground. Mists and vapours slither like ghosts through the

corridors; water and slime drip from the ceilings and walls; the air is dank,

bone-chilling.

Even with electric

lights the tunnels disappear abruptly into the mysterious sepulchral darkness

of twenty centuries.”

Deiss, in his

Author’s Note, makes a point of thanking the custodians, who were unfailingly

polite and helpful – even on the hottest days, after closing hours, and

especially on the harrowing occasion when all the lights shorted out in the

damp Theatre tunnels ninety feet below the surface.”.

See Deiss, J.J. (1968. Herculaneum: a city returns to the sun. London, The history Book Club, (p. x, p.137).

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2009. Cavea. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009. Cavea. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009. Central cavea of the theatre. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre. Early 1800s painting by Giacinto

Gigante. “Veduta della parte

centrale della cavea del teatro di Ercolano”.

See Fino, L., 1988. Ercolano e Pompei. Vedute neoclassiche e

romantiche, Napoli, p. 136.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009.

Central cavea of

the theatre, see above painting by Gigante. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum

Theatre. 1827 picture of Excavation du Theatre d’ Herculaneum.

See Le Riche J. M., 1827. Vues des monumens antiques de Naples. Paris :

Bruere, Ch. 2, pl. 8.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009.

Central cavea of

the theatre, see above painting by Gigante. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre. 1815

painting by Louis Nicolas Lemasle

“Figli di Murat visitano gli scavi di Ercolano”.

Photo courtesy of ICCD. Licence CC BY-SA 4.0.

Now in Museo

nazionale di Capodimonte. Inventory number OA 4720.

Herculaneum Theatre. Pencil sketch by J.M.W. Turner of inside the Herculaneum theatre.

In 1819, very little of the site had been uncovered and the rough nature of Turner’s studies reflect the fact that they were drawn in poorly lit, subterranean surroundings.

Now in the Tate Gallery. See Tate Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported).

See Tate:

Turner sketches of theatre from 1819

“The orchestra now

lies 26.60 metres below the level of the modern Corso Ercolano.

Before us is the

front of the proscenium of the usual

type, with round and square niches deprived of their decoration and minor

sculptures.

At the two

extremities of the proscenium, near

the pilasters of the main entrances to the orchestra (parodoi), there remain the bases of two honorary statues (the

statues either were never found or were removed during the first disordered plundering

of d’Elboeuf)”.

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum,

(p.73).

(Definition of the proscenium, the proscenium was the stage area immediately in front of the scene

building.

It also could be

the row of columns at the front of the scene building, at first directly behind

the circular orchestra, but later upon a stage.)

Gallery of the

media cavea. Faux ashlar decoration of the outer wall of the versurae. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

See Esposito, D., 2014. La Pittura di Ercolano.

Roma: L’erma di Bretschneider, Tav. 30 Fig. 4.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023. Galleria della media cavea. Dettaglio di decorazione in

finto bugnato del muro esterna delle versurae.

Gallery of the media cavea. Detail of Faux ashlar

decoration of the outer wall of the versurae. Photo

courtesy of Johannes Eber.

See Esposito, D.,

2014. La Pittura di Ercolano. Roma: L’erma di Bretschneider, Tav. 30

Fig. 4.

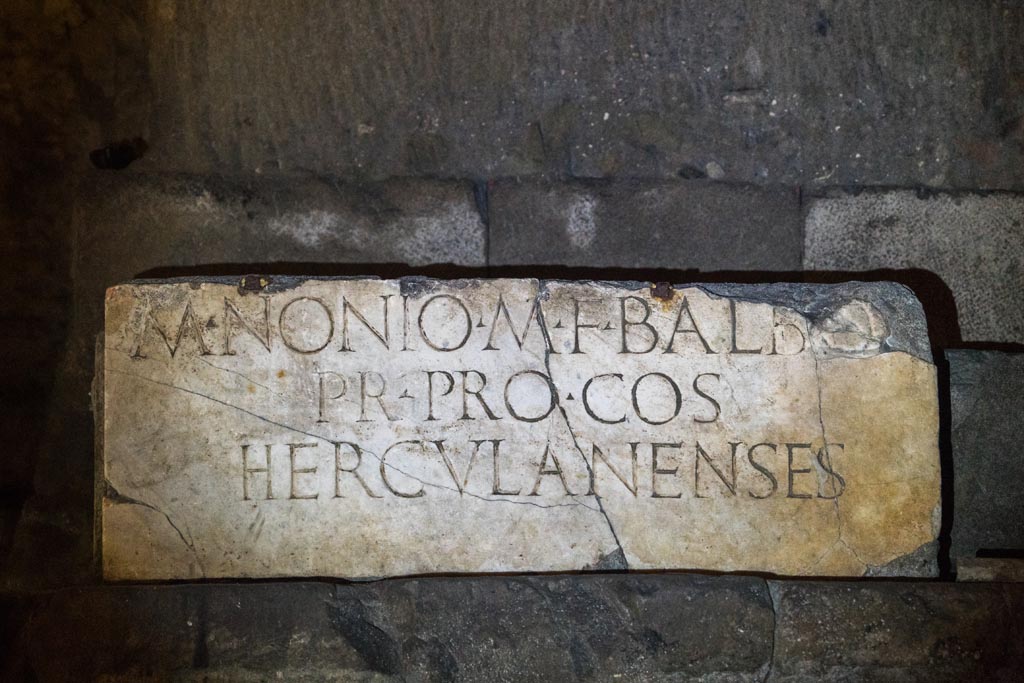

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023. Looking towards base with honorary inscription to M

NONIO M F BALBO at east end of proscenium. Photo

courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. Column capital on brick wall at east end of proscenium.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023.

Front of east end of proscenium with

square and round niches. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. Visiting the remains of the Herculaneum Theatre, painting by G. Gigante.

Wikipedia describes

“In ancient Rome, the stage area in front of the scaenae frons (equivalent to the Greek skene) was known as the pulpitum, and the vertical front dropping from the stage to the orchestra floor, often in stone and decorated, as the proscenium, again meaning “in front of the skene”.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2009. Proscenium and Pulpitum. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

“Upon ascending one of the little

side-stairs which connect the orchestra with the pulpitum, there are still to be glimpsed the skeletal remains of

the mural structure of what was once the magnificent architectonic façade of

the scene (scaena).”

See Maiuri, p.74

(Definition of pulpitum, the stage for actors.)

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2009. East end of

the Proscenium. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre, July 2009. Proscenium.

Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. Steps at east end of proscenium.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre.

October 2023. Marble base with copy of inscription

to M. Nonio M F Balbo, in situ underground. Photo

courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. Side of marble base with copy of inscription to M. Nonio M F Balbo, in situ underground.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre.

October 2023. Copy of inscription to M. Nonio M F Balbo, in situ

underground. Photo courtesy of

Johannes Eber.

![Herculaneum Theatre. Copy of inscription to M. Nonio M F Balbo, in situ underground.

M(arco) Nonio M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

pr(aetori) proco(n)s(uli)

Herculanenses [CIL X 1427]

“One base with the above inscription testifies the public gratitude of the city to that Marcus Nonius Balbus, and of whom we possess the equestrian statue found together with others of the same family in another public edifice, the so-called Basilica.”

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum, (p.74).

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, the people of Herculaneum.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D66, p. 94.

This inscription, opposite that for Appius Claudius Pulcher, may mark the place where an honorific chair was set up in memory of Marcus Nonius Balbus.

A second honorific chair was set up for Appius Claudius Pulcher.](Herculaneum%20Teatro_files/image051.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. Copy of inscription to M. Nonio M F Balbo, in situ underground.

M(arco) Nonio

M(arci) f(ilio) Balbo

pr(aetori)

proco(n)s(uli)

Herculanenses [CIL X 1427]

“One base with the above inscription testifies the public gratitude of the city to that Marcus Nonius Balbus, and of whom we possess the equestrian statue found together with others of the same family in another public edifice, the so-called Basilica.”

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum, (p.74).

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Marcus Nonius Balbus, son of Marcus, praetor, proconsul, the people of Herculaneum.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D66, p. 94.

This inscription, opposite that for Appius Claudius Pulcher, may mark the place where an honorific chair was set up in memory of Marcus Nonius Balbus.

A second honorific chair was set up for Appius Claudius Pulcher.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of decoration on wall of upper part of arch.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of architectural decoration on wall of arch.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of decoration in upper part of arch.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of decoration in arch.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of decoration.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023. East Parascenium, detail of decoration of arch.

Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023.

Looking across proscenium

towards

base with honorary inscription, at far end. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum

Theatre. October 2023.

Looking across west end of the proscenium

towards

base with honorary inscription. Photo courtesy of Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre. October 2023.

Inscription to AP Claudio C F Pulchro after his death, in

situ underground. Photo courtesy of

Johannes Eber.

Herculaneum Theatre, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Inscription to AP Claudio C F Pulchro after his death, in situ underground. Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum

Theatre. 1827. Painting by Giacinto Gigante

“Parte del proscenio del Teatro di Ercolano”.

The inscription to Appius Claudius Pulcher can be seen.

See De Jorio A, 1827. Notizie su gli scavi di Ercolano, Tav IV.

![Herculaneum Theatre. Copy of inscription to AP Claudio C F Pulchro after his death, in situ underground.

Ap(pio) Claudio C(ai) f(ilio) Pulchro

co(n)s(uli) imp(eratori)

Herculanenses post mort(em) [CIL X 1424]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Appius Claudius Pulcher, son of Gaius, consul, hailed victorious commander. The people of Herculaneum after his death.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D65, p. 94.

This inscription, opposite that for M. Nonius Balbus, may mark the place where an honorific chair was set up in memory of Appius Claudius Pulcher.

A second honorific chair was set up for Marcus Nonius Balbus.

Another, earlier, inscription was found on an architrave.

Appius Pulcher C(ai) f(ilius) co(n)s(ul) imp(erator) VIIvir epulon(um) [CIL X 1423]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

Appius Pulcher, son of Gaius, consul, hailed victorious commander, one of the board of seven for feasting.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D64, p. 93.

“The other statue base with inscription, above, is dedicated to Appius Claudius Pulcher, who was consul in the year 38 B.C.”.

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum, (p.74).

Corti wrote – “Finally, there was an enormous marble slab, about five feet high and fifteen feet long. This was laboriously moved until it could be wound up the well on a windlass, and when it was cleaned it was found to have great letters, almost a foot tall, let into it in metal. It was an inscription in Roman capitals, bearing the name of Appius Pulcher, son of Caius, who lived about 38BC., in the year when Caius Norbanus Flaccus was Roman consul. Pulcher was in correspondence with Cicero and succeeded him as governor of Sicily”.

See Corti, E.C.C. (1951). The Destruction and Resurrection of Pompeii and Herculaneum, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, (p.102)](Herculaneum%20Teatro_files/image066.jpg)

Herculaneum Theatre. Inscription to AP Claudio C F Pulchro after his death, in situ underground.

Ap(pio) Claudio

C(ai) f(ilio) Pulchro

co(n)s(uli)

imp(eratori)

Herculanenses

post mort(em) [CIL X 1424]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

To Appius Claudius Pulcher, son of Gaius, consul, hailed victorious commander. The people of Herculaneum after his death.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D65, p. 94.

This inscription, opposite that for M. Nonius Balbus, may mark the place where an honorific chair was set up in memory of Appius Claudius Pulcher.

A second honorific chair was set up for Marcus Nonius Balbus.

Another, earlier, inscription was found on an architrave.

Appius

Pulcher C(ai) f(ilius) co(n)s(ul) imp(erator) VIIvir epulon(um) [CIL X 1423]

According to Cooley and Cooley, this translates as

Appius Pulcher, son of Gaius, consul, hailed victorious commander, one of the board of seven for feasting.

See Cooley, A. and M.G.L., 2014. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge, D64, p. 93.

“The other statue base with inscription, above, is dedicated to Appius Claudius Pulcher, who was consul in the year 38 B.C.”.

See Maiuri, A, (1977). Herculaneum, (p.74).

Corti wrote – “Finally, there was an enormous marble slab, about five feet high and fifteen feet long. This was laboriously moved until it could be wound up the well on a windlass, and when it was cleaned it was found to have great letters, almost a foot tall, let into it in metal. It was an inscription in Roman capitals, bearing the name of Appius Pulcher, son of Caius, who lived about 38BC., in the year when Caius Norbanus Flaccus was Roman consul. Pulcher was in correspondence with Cicero and succeeded him as governor of Sicily”.

See Corti, E.C.C. (1951). The Destruction and Resurrection of Pompeii and Herculaneum, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, (p.102)

Herculaneum Theatre. April 2023.

Bronze stool. Sella curule. Sgabello in bronzo n. 1.

Now in Naples

Archaeological Museum, inventory number 73152. Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

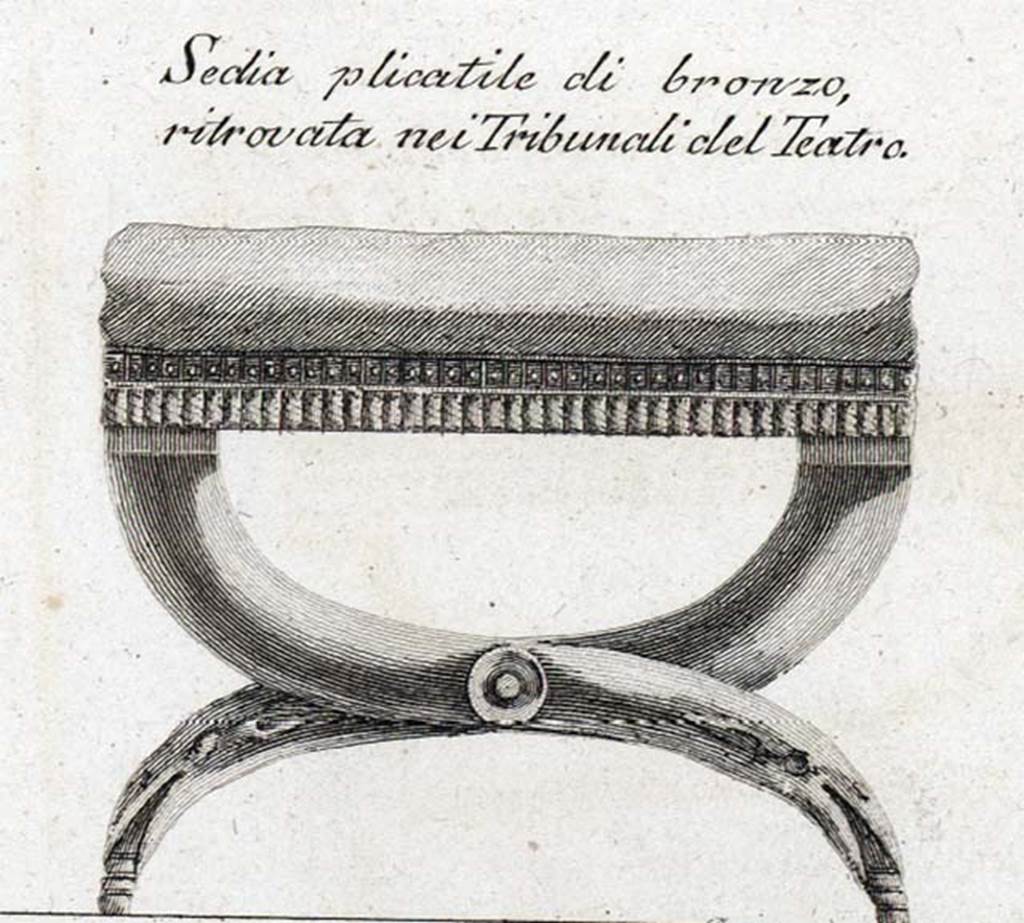

Herculaneum Theatre. Bronze seat found in the tribunal of the theatre.

See Piranesi, F, 1783. Teatro di Ercolano, Tav. IX.

An honorific chair was set up in memory of Appius Claudius Pulcher.

A second honorific chair was set up for Marcus Nonius Balbus.

Herculaneum Theatre.

April 2023. Second bronze stool. Sella curule. Sgabello in bronzo n. 2.

Now in Naples

Archaeological Museum, inventory number 73153. Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

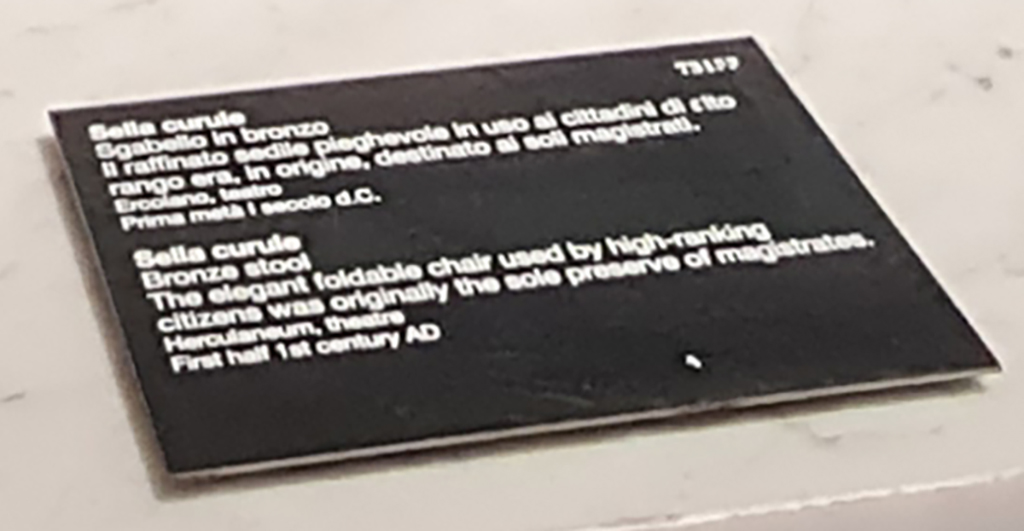

Herculaneum Theatre.

April 2023. Descriptive card. Second bronze stool. Sella curule.

Scheda descrittiva. Sella curule. Sgabello in bronzo.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

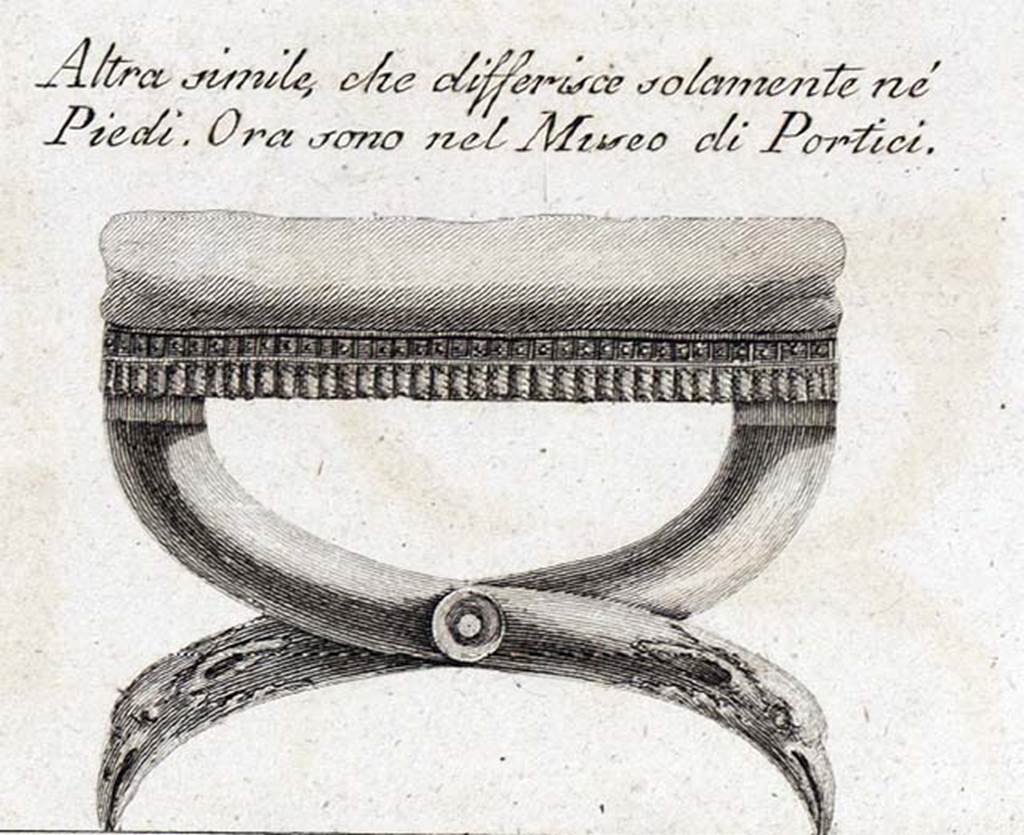

Herculaneum Theatre. Second bronze seat found in theatre. Only the feet differ from the other seat.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum.

See Piranesi, F,

1783. Teatro di Ercolano, Tav. IX.

An honorific chair was set up in memory of Marcus Nonius Balbus.

A second honorific chair was set up for Appius Claudius Pulcher.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009. Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Herculaneum Theatre,

July 2009.

Tunnel with

electricity, and daylight at its end! Photo courtesy of Sera Baker.

Ethel Ross Barker,

wrote in 1908 –

“We enter the Royal

Excavations at Portici, traverse some long modern corridors and finally passing

out of the brilliant sunshine, we descend a hundred modern steps into an

atmosphere growing even colder and damper. Our only light is from an ancient

shaft overhead to the right.

At the foot of the steps we find ourselves in a low, narrow vaulted passage

hewn out of the lava.

It describes about

a quarter of a circle. Fragments of white marble, stained green with damp,

cling to the naked walls, and here and there the eye dimly discerns, in the

fitful glare of the torchlight, a line of a frieze, a delicate piece of

cornice, or the acanthus leaves of a Corinthian pilaster.

This vaulted

passage is the upper corridor of the Theatre, above the media cavea.

We then descend

some ancient steps, which we find to be one of the seven flights dividing up

the cavea, and on the right of the steps we see portions of the tiers of seats

where the spectators sat, all of dull, yellowish-brown volcanic tufa, and the

whole seems hewn out of the living rock. When we reach the bottom of the stairs we see fragments of the thick slabs of giallo antico

still in position on the floor of the orchestra, as they were laid down twenty

centuries ago. The swift feet of the dancers pass no more over its polished

surface, but the marbles are still there, triumphant in their ancient beauty

over time and earthquake and the rapacity of man. To the right of the

orchestra, supported on a vault, a small portion of the tribunal can be seen,

projecting out of the massy lava. The whole of the pulpitum, still covered with a few fragments of marble, and the two

flights of four steps, for ascending from the orchestra to the stage, are

complete. The entire length of the very large stage can be seen. All the niches

and the arches of the proscenium exist but are robbed of their marbles.

Behind the stage is the dressing room for the actors, with a smaller room, apparently for the same purpose, and on the left of the stage is a fine arched doorway for the entrance. The pilasters still retain a portion of their stucco covering, painted red, and on the walls of the dressing room are fragments of colouring to imitate marble. On the right of the stage is the pedestal, with an inscription, that bore the fine statue of the elder Balbus robed in the toga, which is now in Naples Museum. On the left of the stage is a similar inscribed pedestal for an equestrian statue to Appius Pulcher. The statue no longer exists.

A very small portion of the lower part of the outside of the Theatre can be seen, with its tufa and brick walls still adorned with fragments of pilasters, coated in red stucco. In the portion adjoining the left of the stage there is a door for the entrance of the public.”

See, Barker, E. R. (1908). Herculaneum. London, Adam and Charles Black, (p.46-48).

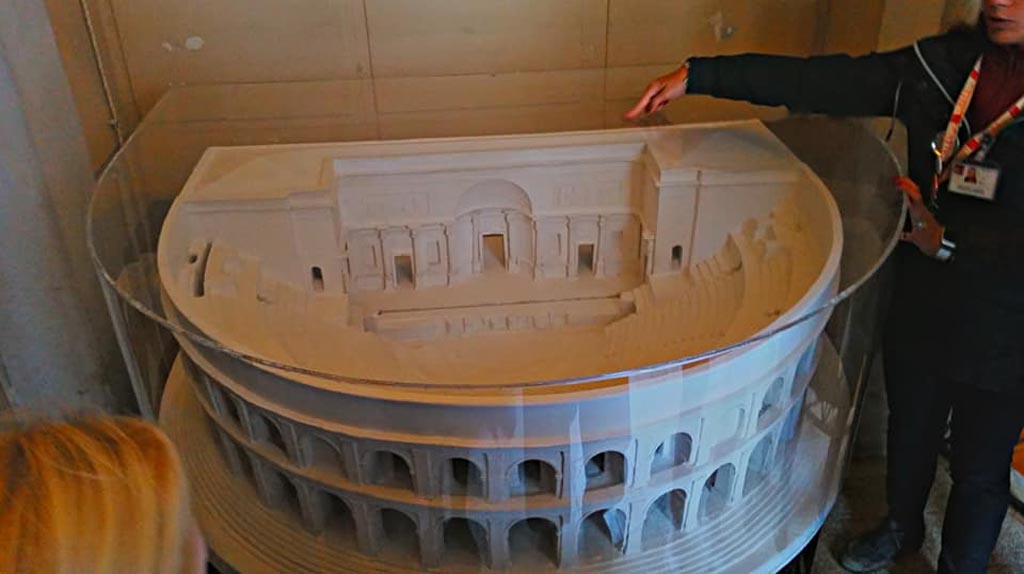

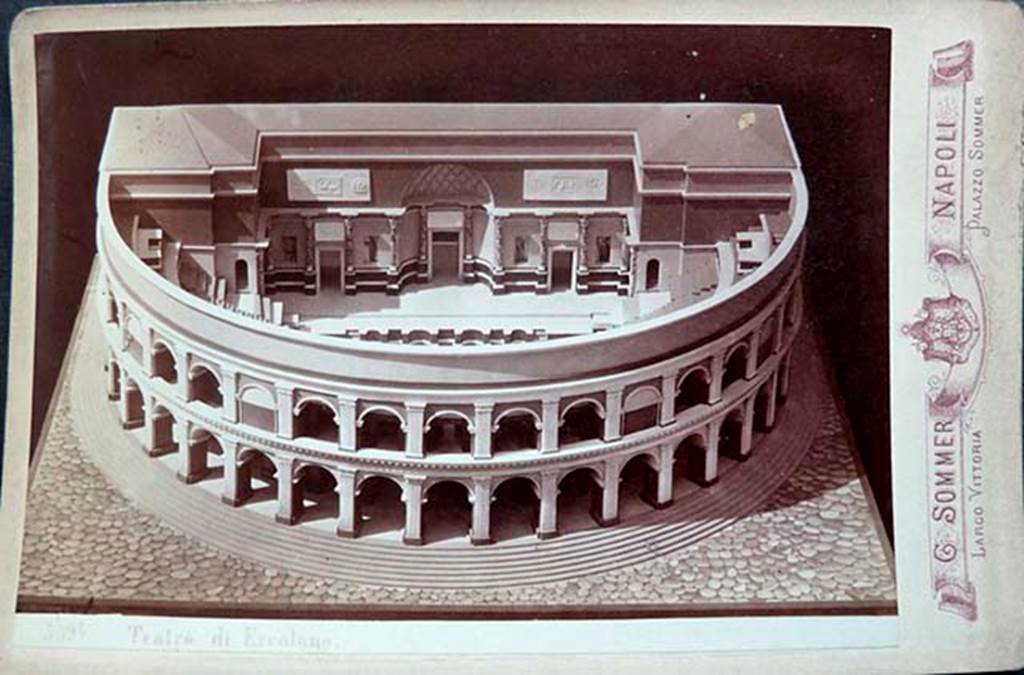

Herculaneum Theatre, photo taken between

October 2014 and November 2019. Model of theatre. Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Herculaneum Theatre. Old photograph by G. Sommer showing a model of the theatre.

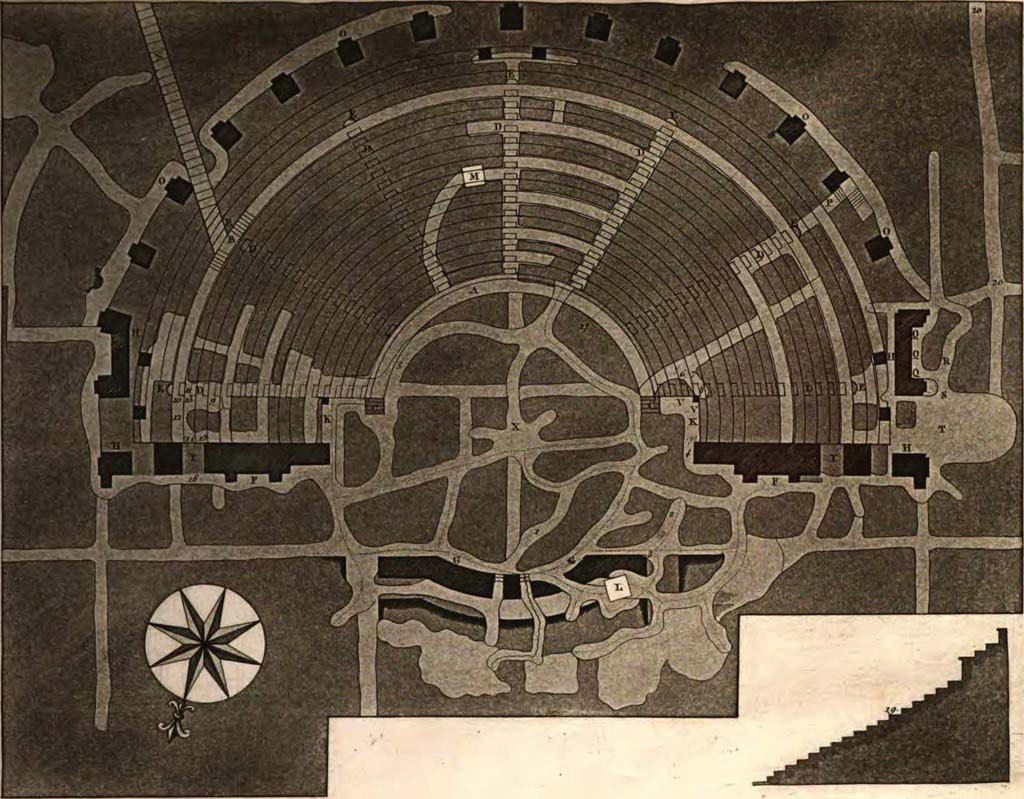

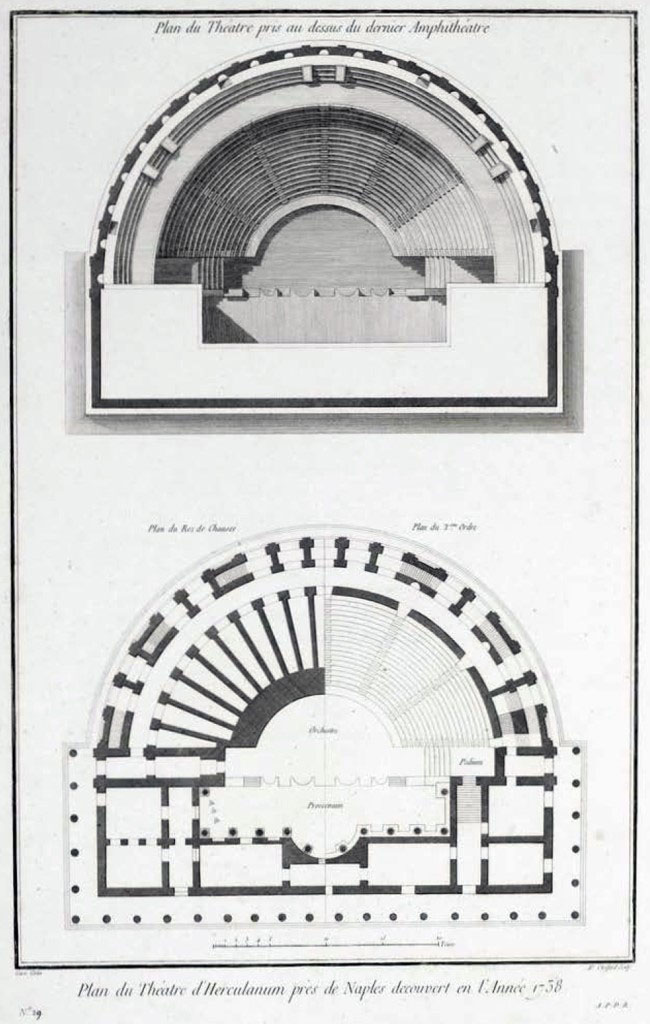

Herculaneum Theatre. 1754 plan by Bellicard showing original well hole in the centre that led to its discovery.

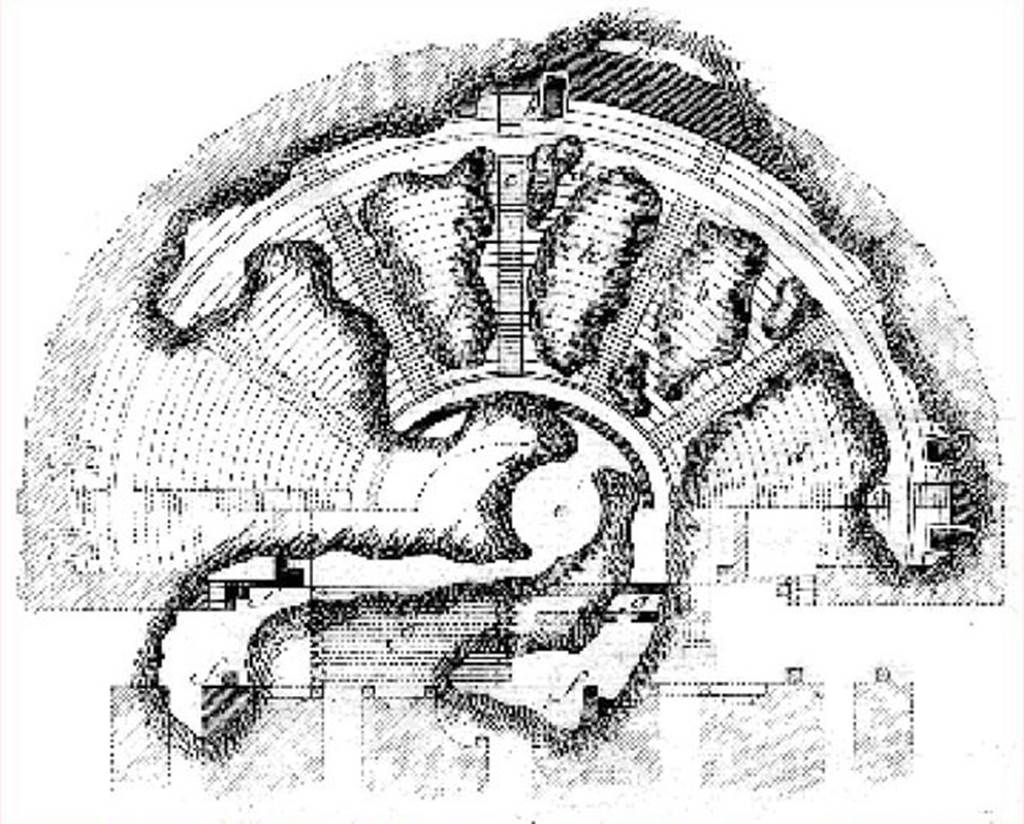

Herculaneum Theatre. 1739 Theatre plan attributed to Rocco Joachim de Alcubierre.

According to Parslow, “The plan and cross section of the theatre was drawn by Alcubierre about 1739 but not engraved until March 20, 1747.

The numbers and letters were keyed to a legend that was printed separately.

L marks the shaft used first by d’Elboeuf, while the dotted lines indicate his tunnels.

N is the later stairway giving access to the site.

Q is the niche in the exterior façade from which Alcubierre removed 3 togate statues.

20 is the tunnel heading in the direction of the Basilica.”

Vedi piano e spiegazione più grandi Pianta

See larger plan and key Plan

See Bullettino Archeologico Italiano, Anno

Primo, num. 5, luglio 1861, pp. 34-5.

See Parslow C. C., 2011. Rediscovering Antiquity. Cambridge University Press, p. 61.

See Ruggiero M., 1885. Storia degli scavi di Ercolano ricomposta

su' documenti superstiti.

Napoli: Acc. Reale delle Scienze, Tav IV.

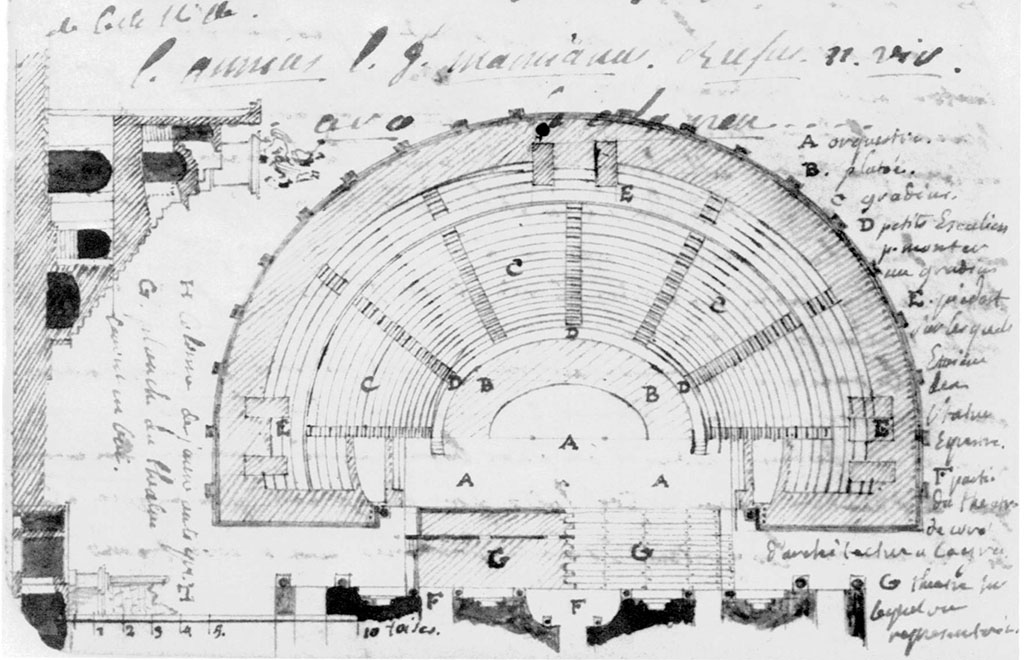

Herculaneum Theatre. Sketch plan drawn in 1750-1 by Jerome-Charles Bellicard in his notebook, p.3.

Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.

See Metropolitan Museum Journal 25.

Herculaneum Theatre. 1782 Plan from Saint Non.

Saint Non, A.,

1782. Voyage Pittoresque de Naples et de Sicile: Vol

1, Partie 2, n.29.

360-degree views of Theatre

See Brian Donovan's 360 degree views of the theatre

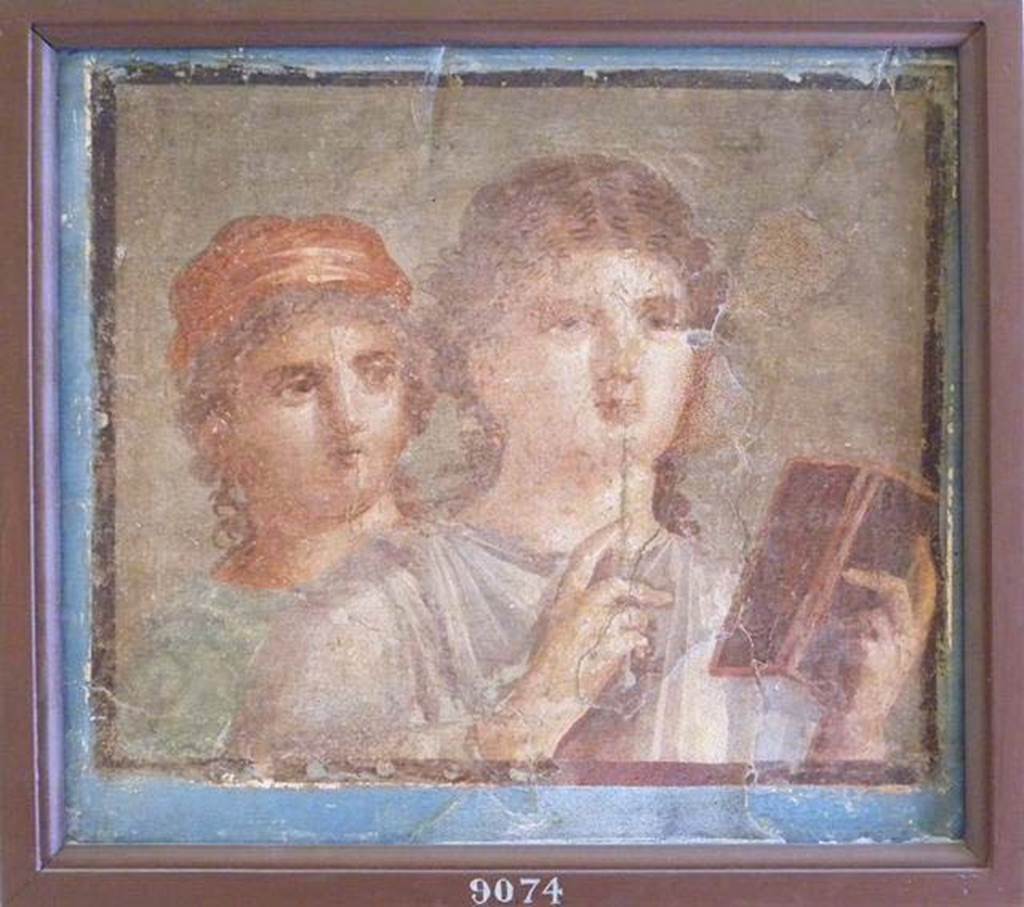

Fresco from the theatre.

Herculaneum Theatre. Found 16th February 1740. Painting of a man and a woman or two women with a writing tablet.

According to AdE, this showed two women both with pearl earrings and hair down to the shoulders.

The front woman was dressed in white and holds an open writing tablet in her left hand and a stylus in her right, which she was pointing towards her lips.

The rear woman was dressed in iridescent green and has a yellow band on her head.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 9074.

See Le Antichità di

Ercolano esposte Tomo 3, Le Pitture Antiche di Ercolano 3, 1762, Tav 46, 239. No

date.

See Pagano, M. and Prisciandaro, R., 2006. Studio sulle provenienze degli oggetti rinvenuti negli scavi borbonici del regno di Napoli. Naples: Nicola Longobardi, p. 184.

Herculaneum Theatre. Found 16th February 1740. Painting of two women with a writing tablet.

See Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte Tomo 3, Le Pitture Antiche di Ercolano 3, 1762, Tav 46, 239. No date.

Found in the Scavi di Portici.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Alcubierre 1739 plan with full key